On this page:

Geology & Geography

The Acropolis rock is part of a Late Cretaceous limestone ridge (Higgins, 29) that cuts through the Attica plateau in the northeast to the southwest axis and includes the Likavitos hill, the Philopappos (Museum) hill, the hill of the Nymphs, and the Pnyx.

The rock rises from the basin about 70 meters and levels to a flat top 300 meters long by 150 meters wide. Its flat top is due to the numerous landfills that have accommodated construction of fortifications and temples since the Mycenaean era.

With its many shallow caves, the abundant percolating water springs and steep slopes, the Acropolis was a prime location for habitation and worship for Neolithic man.

Acropolis in Greek literally means “the highest point of the town”.

While virtually every city had an Acropolis, like Mycenae and Tyrins, the Athenian citadel became synonymous with the word in the minds of most people during the last two millennia.

The Acropolis is located in Southern Europe, in the city of Athens, in the Attica prefecture of Greece.

The City of Athens

Athens was a thriving Mycenaean center that very early in its existence became the center of a “synoikismos”, an alliance and peaceful coexistence of all the adjacent towns.

According to legend, king Theseus united the towns into one administrative entity, and this synoikismos appears to be instrumental in the city’s survival when all other Mycenaean centers were destroyed around 1200 BCE by invading hordes from mainland Greece, or due to a possible invasion of tribes from the North (what many refer to as the Doric invasion).

While all other Mycenaean centers, including mighty Mycenae, were deserted during this period, Athens was the only town to remain inhabited and active. According to tradition, the city owes its survival to the heroic personal sacrifice of king Kordos.

In subsequent years Athens was ruled not by one king but by a group of men, the Aristocrats. Administrative functions moved away from the Acropolis towards other parts of the city where later the Agora developed.

The Acropolis then became exclusively a place of worship and never hosted another ruler, partly because the new realities of city administration made it inconvenient, and partly because the Athenians wanted to eliminate all references to a monarchy.

Stone & Bronze Age

The chronicle of the Acropolis of Athens is lost in prehistory, to a time even before the plane of Attica began to be cultivated.

While the area around Attica was inhabited during the Upper Paleolithic period (30000 – 10000 BCE), archaeological evidence suggests that the small caves around the Acropolis rock and the Klepsythra spring were in use during the Neolithic Period (3000-2800 BCE).

During the Bronze Age, The Mycenaean civilization established many important centers, one of which was Athens. During this time, small towns developed around a fortified citadel where the king resided and controlled the surrounding area.

The first inhabitants we can trace to the Acropolis of Athens were Mycenaean Kings who fortified the rock with massive eight-meter tall walls, and built their palaces there in the 14th century BCE.

Very little remains from these buildings today, but the most obvious evidence of this era is still visible at the southwest end of the Acropolis, right behind the later Temple of Athena Nike, next to the Propylaia, in the form of a cyclopean wall that was built as part of the fortifications.

According to Dontas, Mycenaean kings built a palace at the north end of the rock “where the Archaic temple of Athena was later built, or a little further east on the summit of the hill” (The Acropolis and its Museum, 6).

Besides a fort and a place of royal residence, the Acropolis functioned as a place of worship for the Goddess of fertility and nature, and for her companion male god Erechtheus.

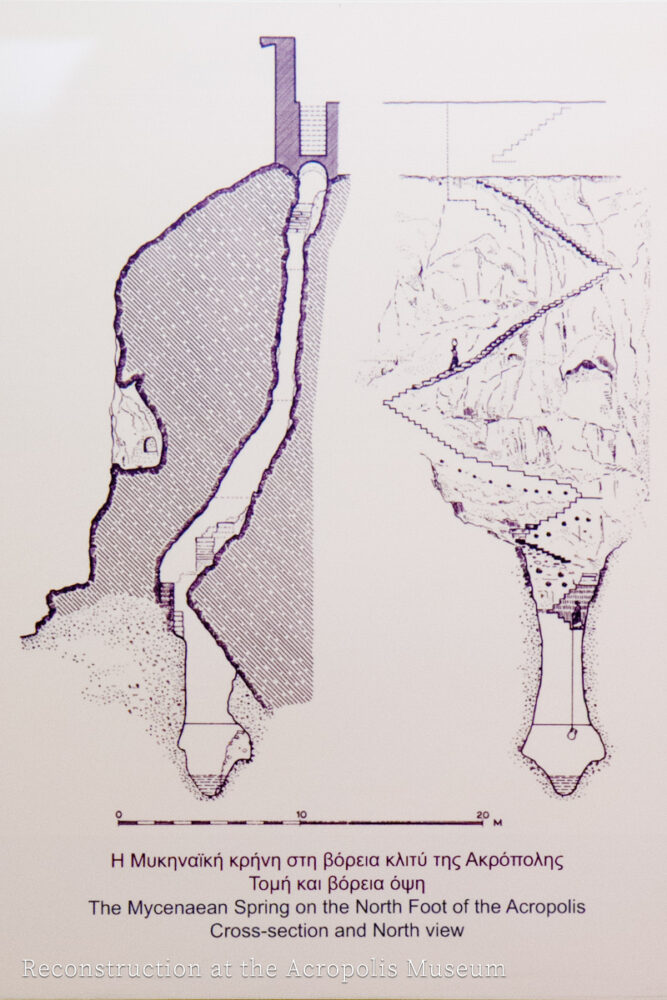

Just like Mycenae and Tyrins, the Acropolis of Athens had its own underground water supply in the form of a deep well, dug at the north end of the rock, which could be used by the defenders during a siege.

Archaic Era

During the 7th c. BCE monumental sculpture and architecture began its development in mainland through a number of building projects in the Acropolis of Athens, at cape Sounion in the southern tip of Attica and in other sanctuaries around Greece.

At the Acropolis of Athens, a larger Doric temple replaced the temple of Athena from the Geometric era. Since no definitive foundations of this building have been found, its exact location and plan remain unknown.

It was adorned with impressive sculptures on its pediment: two lioness killing two calves, marking the first time a temple was pediment, though only on the East end of the building.

During this period, another temple dedicated to Athena was built at the place of the current Parthenon, and a large ramp was built at the Propylaia.

Early in the 6th c. BCE Solon created a set of laws for the Athenian citizens abolishing the many debts that burdened the lower classes, and re-organizing the distribution of power. Among other reforms, he allowed thetes (ordinary workers) to participate in court juries, and to be able to appeal sentences.

Solon’s reforms paved the way for further political changes that in time developed to the Democracy that defined Athens during the Classical period.

Eventually, during the next few decades the development of buildings on the Acropolis that included two pediments adorned with sculptures, and a peristyle.

By the early 6th c. BCE the buildings were made of limestone with many parts (especially the roof) built with marble. The subject of the ornamental sculpture of the buildings evolved to include mythological episodes instead of the nature scenes of earlier temples, and at the same time they became increasingly anthropocentric. This was a conceptual departure that was instrumental in the development of Classical art.

In the middle of the 6th c. BCE Peisistratos became the most powerful Athenian and he ruled the city with his sons, Hipparchos and Hippias, until his death in 527 BCE.

He curtailed the political influence of the Aristocrats, and limited friction between the classes through tyrannical rule. At the same time he promoted economic growth and promoted the arts through a series of building projects.

During Peisistratos’ rule the old temple of Athena Polias was rebuilt to include a pediment at the west end and marble was introduced as a material at the pediment and the metopes. This new temple was also of the Doric order and it was built of limestone, with the exception of the marble pediment. The sculptures of the temple depicted exclusively mythological events (Gigantomachy), a trend that became prevalent until the classical era.

During the late 6th c. BCE, many smaller buildings and a multitude of statues carved out of marble for the first time were added to the Acropolis. The best-known artwork of this period is the statue of Moschoforos that today is exhibited at the Acropolis museum.

Wealthy aristocrats dedicated a large number of votive Kore statues, and financed most of the building projects of the time as their offering to the gods and the city.

After the death of Peisistratos in 524 BCE, the assassination of Hipparchos in 514 BCE, and the exile of Hippias in 510 BCE, Kleisthenis took power and through far-reaching reforms he paved the way for the first ever Democratic society which began taking shape around 507 BCE.

The votive offerings continued at the Acropolis during the classical era (489 – 323 BCE). The Athenians built a small temple of Athena Nike right next to the Propylaia after winning a war against Boeotia and Chalcis.

Classical Era

The Persian Wars

In 499 BCE Athens participated in the defense of the Ionian colonies in Asia Minor against the Persian Empire, and were among those who sacked Sardis, ensuring thus certain retaliation by the great Asian empire.

The events of the late 6th c. BCE led the transition of Athens into the Classical period. The carefree attitude of Archaic art became more introspective and self-aware as Athens led Greece in the transition to the Classical era.

In 490 BCE the Athenians surprised everyone by winning the battle of Marathon, about 42 Km North of Athens, against the invading Persian army.

After the victory at Marathon the Athenians began construction at the Propylaia and the building of another temple next to the old temple of Athena Polias (fertility goddess). This new temple was dedicate to the Athena Pallas, or Parthenos (virgin) and is known as the first Parthenon.

Only the limestone foundation and few marble columns were put in place before the Persians captured Athens in their second attack ten years later n 480 BCE. They burned the city to the ground and destroyed the temples of the Acropolis.

Shortly later in 480 BCE, under the leadership of Themistokles the Athenians defeated the Persian fleet in the naval battle of Salamis. Next year, in 479 BCE they defeated the Persian army at Plataea with a coalition other Greek city/states, putting an end to Persian empire’s ambitions to annex Greece.

The Athenians buried the remains of their monuments and statues that were destroyed by the Persians around the Acropolis rock, and began the rebuilding process once again.

During this time Piraeus was developed into a major port, and Athens was fortified with walls that encircled the city and protected the roads to its port Piraeus (long walls).

The Athenians after these events enjoyed high prestige in the Greek world and it became the leader of an alliance of the Greek states, the Delian League, which was formed to protect Greece from further Persian attacks.

Under the leadership of Kimon the Athenians built a massive fortification at the South end of the Acropolis, which also acted as a retaining wall to support the expansion of the rock. These modifications resulted to the level top we see today. The Clepsydra (the subterranean fountain at the north slope of the Acropolis known as “thief of water” was constructed during this time, as was the monumental bronze statue of Promachos Athena which was made by the sculptor Pheidias.

Pericles

Perikles, son of Xanthipos became the leader of Athens after Kimon’s death in 450 BCE, and during his leadership Athens enjoyed unprecedented prosperity and extraordinary social, political, and cultural development.

The era of Pericles is known as the Golden Eon of Athens.

With funds appropriated from the donation of the Delian League states, Pericles embarked on an impressive building program that adorned Athens with a splendid array of buildings and art, the likes of which influenced art and architecture for the next two millennia, and are still admired today.

The sculptor Pheidias was chosen to oversee the construction of a multitude of temples and sculptures under a master plan, and the best architects and artists were hired to complete the project. Iktinos, Kalikrates, and Mnesikles were the architects who designed the monuments under the supervision of the sculptor Pheidias.

The construction plan included the Parthenon and the Propylaia on the Acropolis, the Odeion of Perikles, the Long Walls and the Hephestion in Athens, as well as the temple of Poseidon at Sounion.

Peloponnesian War

In 431 BCE constructions at the Acropolis and elsewhere was interrupted by the beginning of the Peloponnesian war, which found Athens and Sparta fighting a conflict that lasted until 404 BCE and was fought in the extended theater of the Mediterranean.

Most of the Athenian and Spartan allies got involved in the war at one time or another, and many states that were resentful of Athenian hegemony took advantage of the chaos in order to revolt against the Delian League alliance.

The war effort was punctuated by the plague that afflicted Athens between 430 and 427 BCE killing one third of its population.

During this turbulent time construction at the Acropolis continued at a slower pace, and the Erechtheion and few other auxiliary buildings was completed during the Peloponnesian war.

Ultimately, Athens suffered a humiliating defeat after a series of miscalculations and a disastrous expedition against Syracuse in Sicily in 413 BCE. Construction on the Acropolis and around Attica stopped when the city fell to the Spartans in 404 BCE and the democratic government was replaced by a group of tyrants.

After the defeat in the Peloponnesian war the Athenians did not stay idle for long. A democratic government quickly replaced the Tyranny imposed by the Spartans, but even though construction at the Acropolis resumed, it never reached high levels again.

Athens rebounded and remained an important intellectual and economic center, but soon was confronted with more challenges by another Greek state: Macedonia.

Alexander the Great of Macedonia made certain that his conquest eclipsed all previous Greek achievements. In the process, Hellenic culture expanded and flourished away from the traditional center of Athens and the other city-states of the Classical era.

Hellenistic, Roman, & Byzantine Eras

During the Hellenistic era, the King of Pergamon, Eumenes II, commissioned the Pedestal of Agrippas to support a composition of four bronze sculptures. A few minor buildings were added, and some modifications of existing structures also occurred during this time.

During the Roman period Augustus built a small circular temple a little to the East of the Parthenon, Claudius commissioned a grand staircase that led to the Propylaia, and Hadrian ordered major repairs for the damaged by fire Parthenon.

In 267 CE an invasion by the Herouloi (a band of Germanic tribes) had catastrophic results for Athens.

The Teutonic hordes razed the entire city to the ground. It was a blow that it took Athens 200 years to recover from.

In the 4th century CE Teodosius II and his wife Eudoxia the Athenian commissioned a series of important buildings around Athens. The city thrived as it became the intellectual playground for Christians and Pagans alike, and the Neo Platonic academy was founded South of the Acropolis to accommodate an expanding influx of students.

Under Justinian however, Christianity was imposed on the city in 529 CE and all Pagan remnants, including all the philosophy schools, were closed forcing Athens to become a provincial town with little culture or influence.

The Parthenon was converted to a Christian church dedicated to the Agia Sophia (Devine Wisdom). The Erechtheion also became a Christian church.

Devastating raids by Slavs and Saracens shortly thereafter aided the demise of Athens that lasted until 1000 CE when it became a thriving metropolis once again.

Medieval & Ottoman Era

In 1205 CE the Francs occupied Athens. They turned the Acropolis into a fortress and ruled the city from the Propylaea, which they converted into a palace. At the same time they transformed the Parthenon into a Catholic cathedral, the Notre Dame d’ Athenes.

The subsequent occupation of the Ottomans came almost 2000 years after the Parthenon was built, and at the time it was by all accounts still intact. The Turks occupied Athens in 1458 CE. During their occupation, several monuments were altered. The Parthenon was converted to a mosque, the Erechtheion became a harem, and parts of the Propylaia were damaged “either struck by lightning or due to the explosion of a shell” (Dontas, The Acropolis and its Museum, 16).

After the Turks failed to take Vienna in 1683, Austria, Poland, the Pope, and Venice, allied with the goal of re-conquering all European lands that the Ottomans occupied. The mercenary army that was assembled for the task (often referred to as the “Venetian” army) under the command of the Venetian Morosini freed Moreas (Peloponnese) and in 1687 landed in Athens as the occupying Turks fortified themselves on the Acropolis. The Venetians camped and set up their artillery at the nearby Olympieion. “The battery was commanded by Antonio Muitoni, Conte di San Felice, and the artificer’s name was Sergeant di Vanny” (The Carrey Drawings of the Parthenon Sculptures, 30).

During the ensuing siege the Acropolis suffered from continuing bombardment that lasted for eight days, and on September 26, 1687 a Venetian mortar shell scored a direct hit on the Parthenon that the defending Turks were using as a storage magazine for their gunpowder. The explosion blew apart the long sides and roof of the Parthenon. The ensuing fire lasted for two days, leaving the building in the skeletal state we see today.

“Heard some curious extracts from the life of Morosini, the blundering Venetian, who blew up the Acropolis of Athens with a bomb, and be damned to him!”

(Byron, 249)

The force of the explosion led the Turks to surrender, and the Venetian general Morosini further damaged the building in his unsuccessful attempt to remove the sculptures of the west pediment.

Once the Turks expelled the Venetians from Athens a year later, the Acropolis was transformed into a city district with many small homes scattered around its ground and a small mosque inside the ruined Parthenon.

The Elgin Marbles

While Greece was under Ottoman occupation, the ambassador of England, Lord Elgin, used his influential position to secure the Ottoman officials’ permission to remove whatever Greek antiquities he desired.

Lord Elgin caused extensive damage to the Parthenon and other monuments of the Acropolis by dislodging and sawing off parts of the ancient buildings to dislocate the sculptures known as “The Elgin Marbles”, now at the British Museum in London. His stated motives were to protect the art from the Ottomans, to enhance England’s Art collection, and to educate the public in his country with “reliable examples” of Classical antiquity. He also saw in the art a lucrative commodity and worked hard to sell it to the British Government.

The frivolously of Lord Elgin’s stated motives compared with the destruction he caused borders on tragic irony.

In 1801 and until 1805, with the help of an Italian painter by the name of Lugeri, and for the next twenty years Elgin removed an immense amount of Greek cultural heritage from the Acropolis, and more specifically from the Parthenon.

“Of the 97 surviving blocks of the Parthenon frieze, 56 are in Britain and 40 in Athens.

Facts from the Greek Ministry of Culture

Of the 64 surviving metopes, 48 are in Athens and 15 in the British Museum.

Of the 28 preserved figures of the pediments, 19 are in London and 9 in Athens.”

Modern Acropolis

In 1821, after three and a half centuries of occupation, the Greeks revolted to overthrow the Ottoman Empire from their land. During the struggle, the Acropolis changed hands several times and the monuments were further damaged as Greeks and Turks alternated positions on the rock until the final liberation of Greece in 1827.

The newly formed Greek government immediately protected the Acropolis from further plundering of its cultural treasures, while all Turkish fortifications on the Propylaia were dismantled. Restoration of the monuments began and the temple of Athena Nike was reconstructed.

Excavations for the construction of the Acropolis Museum at the East end of the rock after 1880 unearthed many Archaic sculptures. The foundations of the old temple which was destroyed by the Persian invasion in 480 BCE were also discovered at this time.

Since the late 19th century, the Acropolis of Athens has undergone systematic excavations and extensive restorations of its buildings.

Errors during the early days of archaeological restorations resulted in monuments being distorted and damaged. Early restorers used steel as a reinforcing element embedded in the marble parts of the buildings. As the metal oxidized over the years, it caused significant damage to the stone around it. Subsequent reconstructions replaced the early steel inserts with titanium ones.

The air pollution at end of the 20th century threatened to destroy in a short time what took eons to erode. Sulfuric acid in the polluted air, mixed with the rainwater reacts with the marble, transforming its surface into a layer of gypsum and causing irreparable damage to the monuments.

Since then, successful steps have been taken to preserve and reconstruct the monuments. The air of Athens has been improved, and many priceless artifacts (like the Caryatids from the Erechtheion and the Parthenon sculptures) have been removed from the buildings to be sheltered in the adjacent Acropolis museum, while exact replicas hold their place on the Acropolis rock.

Timeline of Interventions

As a cultural landmark of fame, as a symbol of Classical ideals, and as a last citadel of the city’s defense, the Acropolis of Athens became the target of numerous destructive events and alterations in the past two millennia.

According to Dr. Korres (“Restoration Work on the Acropolis Monuments“) the following dates represent the times that the acropolis suffered major interventions:

267 CE: Herulian Invasion: Destruction of Athenian Monuments, followed by more destruction from Vandals, and Visigoths shortly thereafter.

Circa 300 CE: The Parthenon underwent repairs that were not professionally supervised and caused more damage by harvesting unrelated stones, re-working and fitting them in different places.

6th Century: transformation of the Parthenon in a Christian Church. Sections of the frieze were removed to create windows for the church.

1180: Renovation of the Christian Church in the Parthenon removed the central section of the entablature, including the central scene of the east pediment to create an enlarged apse for the church.

1205: The Parthenon as a Latin Church

1206: The Propylaea became a late Frankish residence.

1458: The Parthenon converted into a mosque

1640: Explosion of Turkish ammunition destroys the Propylaea.

1687: Venetian Bombardment, explosion of the Parthenon. The defending turks used the mosque inside the Parthenon as an ammunition magazine. A well-placed mortar by the Venetians who were fighting the Turks caused the most damage in the building’s history, and left it largely in the state we see it today.

1800-1805: Lord Elgin caused extensive destruction to the Parthenon and other monuments of the Acropolis by dislodging and sawing off parts of the ancient buildings to dislocate the sculptures known as “The Elgin Marbles”, now at the British Museum in London. His stated motives were to protect the art from the Ottomans, to enhance England’s Art collection, and to educate the public in his country with “reliable examples” of Classical antiquity. He also saw in the art a lucrative commodity and worked hard to sell it to the British Government.

1826: Turkish bombardment, explosion of the Erechtheion.

1834: The Acropolis treated as an archaeological site.

1835, 1860, 1885-1890: Archaeological excavations in the Acropolis.

1842-1844, 1900-1902, 1913, 1922-1933: Restoration of the Parthenon.

1903-1917: Restoration, Erechtheum, Propylaea

1940, 1954-60: Restoration, Temple of Athena Nike, Propylaea, and the Parthenon.

Acropolis Mythology

In constructing the early history of the Acropolis of Athens, it is necessary to consult some of the legends that guided its development over the years.

Athena

Athena (sometimes transliterated as Athene) the goddess of fertility and nature that the Mycenaeans worshiped was eventually replaced by the goddess Athena around 1000 BCE. Athena gave her name to the city of Athens, and she displayed dual nature.

As Athena Polias she was the goddess of wisdom, protecting nature and fertility, while as Athena Pallas, she was a war-maker and a virgin (parthenos).

During the Geometric period (900-700 BCE) she was worshiped at a small temple that was built at the center of the Acropolis, a little to the south of the later Erechtheion. This temple sheltered a Xoanon (wooden statue) that was believed to have fallen from the heavens (Diipetes) as a gift to the city of Athens.

Erechtheus

Erechtheus was a legendary king of Athens who was also a deity. His parents were Gaea and Hephaestus, and he was the great-grandfather of Deaedalos and an ancestor of Theseus. It is after him that the Erechtheion was named.

Kekrops

Kekrops (circa 1600 – 1100 BCE) according to the Athenian legends, was the mythical king of Athens who organized Attica into twelve towns according to Strabo: Aphidna, Brauron, Dekelia, Eleusis, Epakria, Kekropia, Kephisia, Kytherros, Tetrakomoi, Tetrapolis, Thorikos, and Sphettos. In these legends, Kekrops is usually associated with a snake.

Poseidon

Poseidon, the god of the sea and of earthquakes (of which Greece enjoys many) eventualy replaced the prehistoric Erechtheus, although Erechtheus continued to be worshiped alongside Athena on the Acropolis.

Theseus

Theseus was the son of Aegeas (the man who gave his name to the Aegean sea). He is credited with many deeds, most important of which are the slaying of the Minotaur (perhaps symbolizing Athenian freedom from Minoan hegemony), and the unification of all the tribes of Attica into a synoikismos (unity of communities) with Athens at its capital.

Naming Rights

According to a popular myth, Athena and Poseidon competed for the honor of being the patron of the city. The myth describes how the gods provided gifts in order to gain the people’s favor.

Poseidon hit the Acropolis rock with his trident at the place where the Erechtheion was built later, and from the wounded earth a majestic horse arose as a gift to the citizens.

The city however was named after Athena, for she gave the gift of the olive tree.

The myth is indicative of a struggle between major religious currents during the Archaic period in Athens and although Athena dominated worship, ultimately the two gods coexisted peacefully upon the Acropolis rock through temples and legends.

This battle of the gods is depicted in the sculptural arrangement at the west pediment of the Parthenon.

Related Pages