On this page:

Prehistory to Iron Age

The Agora of Athens has been in use since the late Neolithic era, and it was used as a cemetery during the Mycenaean and the later Iron Ages. Excavations have unearthed around 50 tholos tombs with multiple burials from the period between 1600 and 1100 BCE (the era known as Mycenaean), as well as 80 graves containing inhumations and cremations from the Iron Age (1100-700 BCE). In this later period it must have been occupied by residencies as well, judging from the numerous water wells that sprinkled the area.

The area began its history as the heart of the Athenian political and economic engine in the beginning of the 6th c. BCE with its gradual transformation into a public place. The Agora developed over many years with public buildings and workshops sprouting in a relatively flat ground, easily accessible from the center of the city, from the all-important Athenian farmlands, as well as from the port of Pireas. Its growth conformed to the existing ancient roads, especially the Panathenaic way that connected the Dipylon Gate (the main gate of the defensive wall) with the Acropolis.

Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic Eras

From the 6th and until the 1st century BCE the Agora as the heart of the government and the judiciary, as a public place of debate, as a place of worship, and as marketplace, played a central role in the development of the Athenian ideals, and provided a healthy environment where the unique Democratic political system took its first wobbly steps on earth. During this time, the Agora’s political, cultural, and economic influence shaped some of the most important decisions undertaken in the shaping of what we commonly call today Western Civilization.

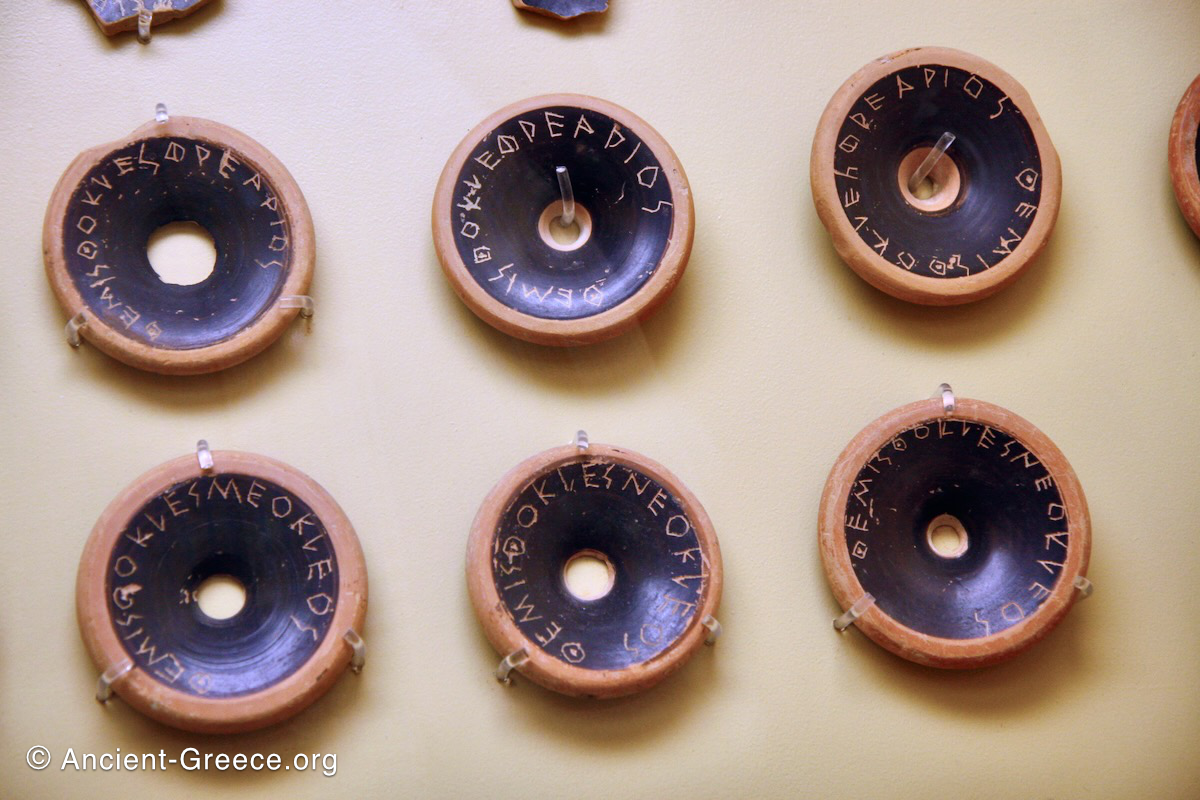

Well structured arguments by the likes of Socrates and Plato echoed in its streets, the courts and prisons enforced Athenian laws, its Mint spread the dominant Athenian drachma coins throughout the Aegean, the Prytanes determined political affairs in the Tholos, and randomly selected Athenian citizens prepared the laws for the assembly in the Bouleuterion.

With a little imagination and knowledge, one can imagine the hustle and bustle of its streets with merchants of all kinds tending their benches in the shade of the Stoas and under cloth tents, with ox cart wheels creaking through the Panathenaic way, and with citizens convening in small groups under the shade of small trees. Horses, stray dogs, citizens, metics, slaves, visitors and foreigners mingled and loitered on the grounds, attentive ears listened to sailor tales from foreign lands, hoplites relayed news from the fronts, and philosophers debated the fine points of arete oblivious to the cacophony rising all around from the energetic artisan workshops and market kiosks.

Once per year, the Panathenaic festival united the Athenians in celebration and solemn procession through the Agora toward the Acropolis. But this imaginative picture of the Agora as an engine of constructive human activity did not last in perpetuity. Its buildings were razed and rebuilt several times through the centuries.

The early buildings, mostly bunched on the west end of the Agora, were destroyed by the Persians in 480 BCE, but soon afterward the entire area was rebuilt to include development in the north, west, and southern areas with the erection of three Stoas–the Poikile, the Southern, and the Stoa of Zeus Eleutherios–, the Tholos, the New Bouleuterion, the Mint, The Dikastiria (law courts), several fountains, along an assortment of artisan workshops. The fine temple of Hephaestus was built on the low knoll of Kolonos Agoraios in 450 BCE as part of the extensive rebuilding of sacred places initiated by Pericles.

The Agora remained a vital place of Athenian life and growth continued until the 2nd c. BCE when the the impressive Stoa of Attalos was dedicated, but eventually, as Athens declined in importance during the late Hellenistic Era so did the development of its Agora.

Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman Times

The Romans under Sulla sacked the Agora in 86 BCE, but later contributed to its growth with impressive buildings programs that lasted until the end of the 2nd century CE. Marcus Agrippa funded the Odeion and probably the Temple of Ares. From the grounds of this temple and from the nearby Areopagos in 52 CE St. Paul introduced Christianity to Athenians and strolled the Agora streets debating with Stoic and Epicurean philosophers.

While St. Paul found the Agora a robust place of assembly, adorned by a myriad of statues of Greek and Roman deities and heroes, a series of subsequent invasions plagued it for the next 700 years.

As a result of its destruction in 267 CE by invading Heruls the Agora stopped functioning as a public place for a long time, especially after Alaric, King of the Visigoths plundered it in 396 CE. A large Gymnasium was erected over the ruins in 400 CE, only to be destroyed once again by raiding Slavs in the end of the 6th century CE. After that, it was deserted for about three hundred years and during this time, the area was buried under a thick layer of mud.

The Christian church of Agioi Apostoloi and few houses were built in the Agora around 1000 BCE. In the 7th century and until the beginning of 19th century, the Temple of Hephaestus was converted into a Christian church dedicated to Ag. Georgios (St. George).

The entire city of Athens had declined to the size of a small village by that time, so after the invasion and sacking of the Agora in 1204 by invaders from the Nafplion it was abandoned for another four hundred years.

After 1821 and for the duration of the Greek revolution, sporadic clashes with the occupying Ottomans in its grounds brought further damage to the existing buildings. According to Camp II (12), during this time the Temple of Hephaestus was converted into a Protestant cemetery where a number of European philhellenes, who died fighting for Greek independence, were buried.

The Modern Era

With the expulsion of the Turks and the establishment of the modern Greek state, the area was quickly urbanized with residential and commercial buildings, but at the same time, beginning in 1831, isolated excavations began around this flurry of construction. Soon, the importance of the area compelled the Greek government to define 121,000 square meters as a dedicated archaeological site, prompting the removal of four hundred contemporary buildings and systematic excavations to begin. In 1832, the day after King Otto took his oath in it, the Hephaisteion became the first Greek archaeological museum.

Between 1953 and 1956, the Stoa of Attalos was rebuild according to the ancient plans to house the fruits of the Agora excavations and the museum where the most important artifacts are put on public exhibition.

The archaeological site today includes a large part of the ancient Agora but much of it still remains buried under the shops of the Monastiraki area. Several coffee shops and restaurants have installed glass floors in their basements (and under their bathrooms nonetheless) so their patrons can glimpse at the ancient ruins beneath.

However, the weaving of modern needs and preservation of the historical heritage is not always so graceful. In 2011, Athenians were called to decide between an expensive renovation of the main Athens-Piraeus railway line and the preservation of one of the most important features of the Classical Agora, the Altar of the Twelve Gods which stood in the way of the main public transportation artery. In the end, despite protests and legal challenges, the courts ruled that the needs of contemporary Athenians prevailed and railway renovations proceeded as planned.

Evidently, despite the austere state of the archaeological site today with scant ruins, and fragments of buildings and objects scattered about, the Athenian Agora continues writing chapters in its history.

Agora Timeline

| Late Neolithic Era | Evidence of early habitation |

| 1600-700 BCE | Area used as cemetery. Evidence of Mycenaean Tholos Tombs and Iron Age graves. |

| 6th c. BCE | Athenian Agora begins developing as a public place |

| 520 BCE | Altar of Twelve Gods, NE Fountain created |

| 508-7 BCE | Old Bouleuterion built, and Agora boundaries established |

| 480 BCE | The Agora is burned by the Persians |

| 5th-4th c. BCE | Rebuilding of the Agora with important public and administrative gildings: Poikile Stoa, Tholos, New Bouleuterion, Stoa of Zeus Eleutherios, Southern Stoa, Mint, Law Court (Dikastiria), several fountains, and workshops. |

| 450 BCE | Temple of Hephaestus built |

| Late 4th c. BCE | Building intensity increases |

| 150 BCE | Stoa of Attalos built |

| 86 BCE | Extensive destruction of the south end by the Romans under Sulla |

| 15 BCE | Agrippa erects the Odeon in the Agora |

| 2nd c. CE | Construction of: Library of Pantainos, the Basilica, the Nymphaion, the Monopteros |

| 100 CE | Ancient Agora connected to the new Roman Agora |

| 267 CE | Sacked by the Heruls |

| 267-400 CE | Agora abandoned. Construction of large houses on the south |

| 400 CE | Gymnasium built over the ruins in the center |

| 580-590 CE | Agora destroyed by Slavic invasions. |

| 7th-10th CE | Agora abandoned and buried under mud |

| 1000 CE | Church of Agioi Apostoloi built. Light construction in area |

| 1204 CE | Area razed by invaders from the Nafplion area |

| 13th-17th c. CE | Agora area abandoned |

| 1826-7 CE | Destruction during the Greek revolution |

| 1836-1931 CE | The Area is heavily urbanized after the creation of the modern Greek state. Limited excavation begins |

| 1931 CE | Excavations include an area 121,000 sq. meters and 400 contemporary buildings removed. |

| 1953-6 CE | Stoa of Attalos reconstruction |

Agora Photos

Related Pages