On this page:

Rediscovering the Temple’s Colors

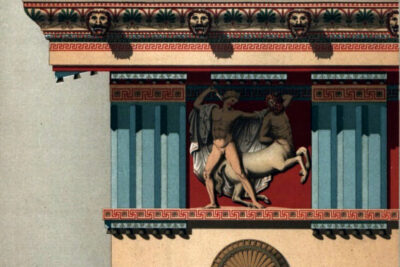

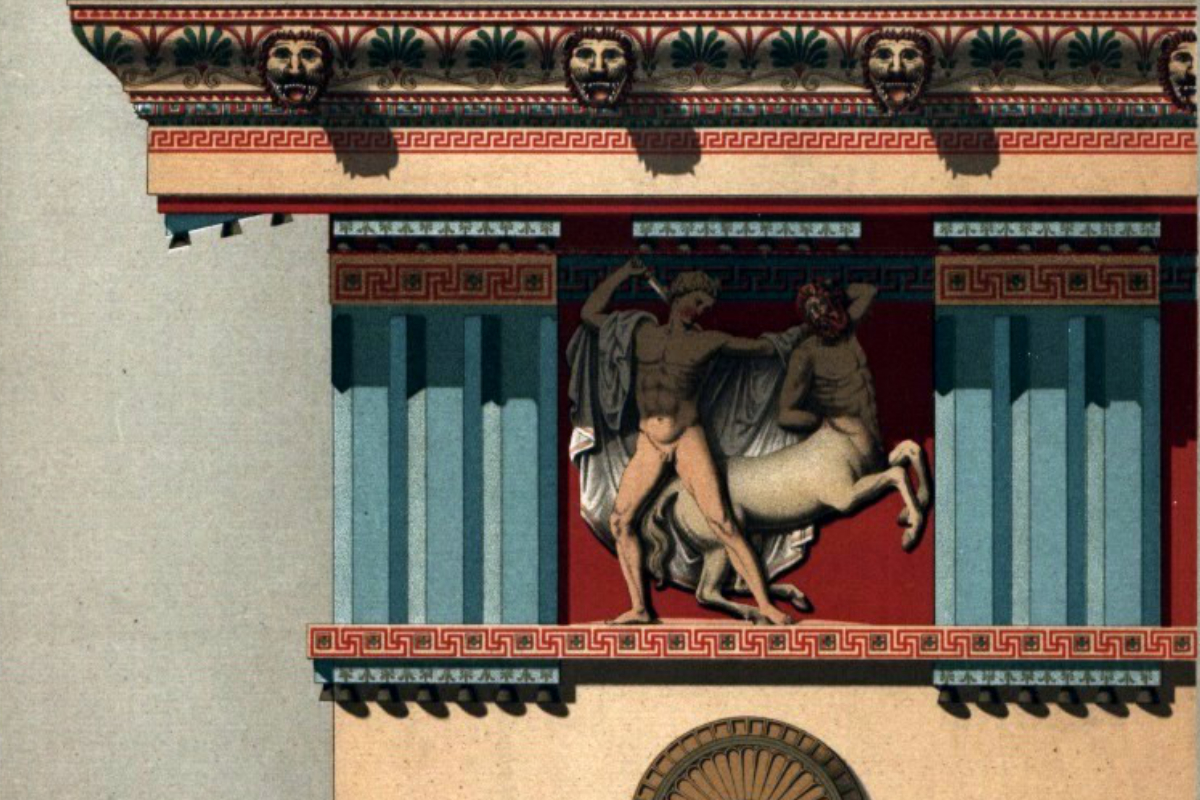

The colors of the Parthenon have washed away over the past 2400 years, but pigment remnants can still be traced on certain surfaces, so we know that the building was colored. But was every surface covered in color? Were the colors vivid, soft like pastel, or a wash like watercolor? We can not be certain.

Several different interpretational drawings have been produced since the 19th century CE. Scholars like Durm, Loviot, Paccard,, Semper, Springer, Windstup, created conflicting educated reproductions, some with vivid, some with bright, and some without much color. But even in their divergence, they provide some guidance on the placement and type of colors and about the polychrome nature of the temple.

Analysis of the temple’s pigment remnants by the Acropolis Restoration Service in 2024 revealed that the flat background of the tested metopes contains remnants of red and red-orange pigment, while the flat bands that frame each at the top and bottom have remnants of blue, including Egyptian blue on the top band. (Αγγελακοπούλου, 1:01:18).

Pigment and Binder

What we know colloquially as “paint” is actually a substance made of “pigment” suspended in a “binder” which is applied as a thin covering on a “substrate”. The pigment provides the color, the binder “carries” and adheres the pigment to a substrate (marble in the case of the Parthenon).

Pigments used on marble in ancient times were derived from colored earth (red, red-orange, yellow, brown ochre), minerals (azurite, malachite, conichalkite, and cinnabar), and chemicall processes (Egyptian blue, lead white, minium, carbon black).

A gross approximation of known color pigments used in Classical Greece:

Earth:

red ochre

red ochre

brown ochre

yellow ochre

Mineral:

cinnabar

azurite

malachite

conichalkite

Chemical:

minium

Egyptian Blue

lead white

carbon black

Microscopic traces of beeswax found alongside pigment on some temple surfaces, along with the inscriptions listing the encaustic painters who were employed on the Acropolis, indicate that the pigments were most likely applied to the marble with wax through the encaustic method, at least on these test spots.

Wax as Binder and Sealant

Wax as a paint binder was used for centuries in ancient Greece. On the Parthenon, pigment was mixed into the molten wax and then applied directly to the marble.

Wax is very versatile and can be thinned or thickened by mixing it with other waxes, turpentine, oils, resins, or fats. It is also a good sealant for moisture, albeit too sensitive to temperature fluctuations.

In Ancient Greece, marble was not left in its raw, “white” state. Once a statue or an architectural element was painted (polychromy), a process called ganosis was applied. In ganosis, a mixture of beeswax and oil (often olive oil) was applied to the surface. It was then rubbed or buffed with clean linen cloths to create a soft, skin-like luster to protected the porous marble and the delicate pigments from moisture and airborne dust.

It also gave the stone a “glow” that mimicked the translucency of human skin, a hallmark of Lysippic and Praxitelean sculpture.

Vitruvius and Pliny note that this finish was not permanent; it had to be reapplied periodically to maintain the protection and sheen.

The Encaustic Method

In Encaustic painting, pigment is mixed in with hot wax. It is also know as “hot wax painting” because using heat is an integral part of the process.

The process of encaustic painting starts with keying (roughing-up) the stone with chisels to facilitate better adhesion of the paint. Evidence of keyed marble with tooth chisel marks under some tested surfaces on the Parthenon add to the evidence that the encaustic method was in use.

Then torches, heated metal spatulas and cloth or leather pads are used to apply and spread the pigmented wax and to smooth its surface.

Slight heating melts the wax into the keyed surface, seals the stone porous and produces a degree of sheen as the top of the mixture is polished, allowing light to penetrate easily all the way to the marble before it carries the color to the viewer’s eyes.

Color was an Integral Part of the Temple

Painting the Parthenon was an important part of the building process, and as the “final touch” it required the services of the best artisans who procured the best materials available for the task. The Erechtheion inscriptions indicate that “ενκαυταί” (encaustic artisans) were paid 5 oboli per foot of completed work.

The temples’ cornice that wraps around the temple has traces of an intricate grid which was used to guide artisans while painting geometric patterns like the meander.

Why the Overall Aesthetic Look Remains Uncertain

Even when we identify specific pigments, the final visual effect of a Greek temple like the Parthenon remains elusive. The aesthetic outcome depended entirely on the application process, which dictates how light interacts with the stone.

- The Buffing Effect: The intensity of the wax-based finish (ganosis) changed the surface texture. High-gloss buffing would produce vivid, saturated colors, whereas a matte finish would diffuse light, making the colors appear soft and flat.

- Pigment Saturation: The transparency of the medium played a crucial role. Low pigment concentrations allowed light to penetrate the wax and reflect off the white marble beneath, creating a luminous, ethereal glow. Conversely, high concentrations resulted in deep, opaque tones.

- Layering and Depth: Unlike modern acrylics that sit on the surface like a “skin,” ancient encaustic (wax-based) and tempera techniques allowed for successive transparent layers. This gave the colored elements a jewel-like depth, similar to polished gemstones, rather than the flat appearance of modern paint.

In conclusion, while we can identify the “palette” of the Parthenon, the final visual impact—its luminosity, depth, and texture—remains a mystery without knowing the precise technical execution used by ancient artisans. And that adds a layer of intrigue to the monument.

Related Pages