On this page:

Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine Eras

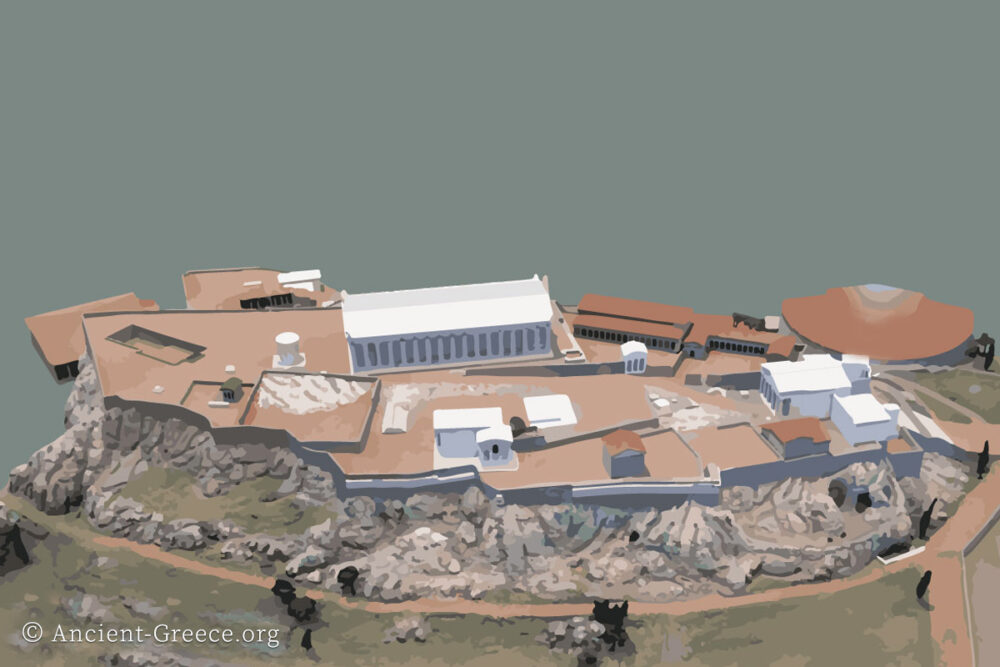

During the Hellenistic era, the King of Pergamon, Eumenes II, commissioned the Pedestal of Agrippas to support a composition of four bronze sculptures. A few minor buildings were added, and some modifications of existing structures also occurred during this time.

During the Roman period Augustus built a small circular temple a little to the East of the Parthenon, Claudius commissioned a grand staircase that led to the Propylaia, and Hadrian ordered major repairs for the damaged by fire Parthenon.

In 267 CE an invasion by the Herouloi (a band of Germanic tribes) had catastrophic results for Athens.

The Teutonic hordes razed the entire city to the ground. It was a blow that it took Athens 200 years to recover from.

In the 4th century CE Teodosius II and his wife Eudoxia the Athenian commissioned a series of important buildings around Athens. The city thrived as it became the intellectual playground for Christians and Pagans alike, and the Neo Platonic academy was founded South of the Acropolis to accommodate an expanding influx of students.

Under Justinian however, Christianity was imposed on the city in 529 CE and all Pagan remnants, including all the philosophy schools, were closed forcing Athens to become a provincial town with little culture or influence.

The Parthenon was converted to a Christian church dedicated to the Agia Sophia (Devine Wisdom). The Erechtheion also became a Christian church.

Devastating raids by Slavs and Saracens shortly thereafter aided the demise of Athens that lasted until 1000 CE when it became a thriving metropolis once again.

Medieval and Ottoman Period

In 1205 CE the Francs occupied Athens. They turned the Acropolis into a fortress and ruled the city from the Propylaea, which they converted into a palace. At the same time they transformed the Parthenon into a Catholic cathedral, the Notre Dame d’ Athenes.

The subsequent occupation of the Ottomans came almost 2000 years after the Parthenon was built, and at the time it was by all accounts still intact. The Turks occupied Athens in 1458 CE. During their occupation, several monuments were altered. The Parthenon was converted to a mosque, the Erechtheion became a harem, and parts of the Propylaia were damaged “either struck by lightning or due to the explosion of a shell” (Dontas, The Acropolis and its Museum, 16).

After the Turks failed to take Vienna in 1683, Austria, Poland, the Pope, and Venice, allied with the goal of re-conquering all European lands that the Ottomans occupied. The mercenary army that was assembled for the task (often referred to as the “Venetian” army) under the command of the Venetian Morosini freed Moreas (Peloponnese) and in 1687 landed in Athens as the occupying Turks fortified themselves on the Acropolis. The Venetians camped and set up their artillery at the nearby Olympieion. “The battery was commanded by Antonio Muitoni, Conte di San Felice, and the artificer’s name was Sergeant di Vanny” (The Carrey Drawings of the Parthenon Sculptures, 30).

During the ensuing siege the Acropolis suffered from continuing bombardment that lasted for eight days, and on September 26, 1687 a Venetian mortar shell scored a direct hit on the Parthenon that the defending Turks were using as a storage magazine for their gunpowder. The explosion blew apart the long sides and roof of the Parthenon. The ensuing fire lasted for two days, leaving the building in the skeletal state we see today.

“Heard some curious extracts from the life of Morosini, the blundering Venetian, who blew up the Acropolis of Athens with a bomb, and be damned to him!”

(Byron, 249)

The force of the explosion led the Turks to surrender, and the Venetian general Morosini further damaged the building in his unsuccessful attempt to remove the sculptures of the west pediment.

Once the Turks expelled the Venetians from Athens a year later, the Acropolis was transformed into a city district with many small homes scattered around its ground and a small mosque inside the ruined Parthenon.

The Pilfering of the Parthenon Marbles by Elgin

While Greece was under Ottoman occupation, the ambassador of England, Lord Elgin, used his influential position to secure the Ottoman officials’ permission to remove whatever Greek antiquities he desired.

In 1801, with the help of an Italian painter by the name of Lugeri, and for the next twenty years Elgin removed an immense amount of Greek cultural heritage from the Acropolis, and more specifically from the Parthenon.

“Of the 97 surviving blocks of the Parthenon frieze, 56 are in Britain and 40 in Athens.

Facts from the Greek Ministry of Culture

Of the 64 surviving metopes, 48 are in Athens and 15 in the British Museum.

Of the 28 preserved figures of the pediments, 19 are in London and 9 in Athens.”

This History of the Acropolis is divided into the following chapters:

- Introduction

- Prehistoric Acropolis

- Archaic Acropolis

- Classical Acropolis

- Post-Classical Acropolis

- Modern Acropolis

Related Pages