On this page:

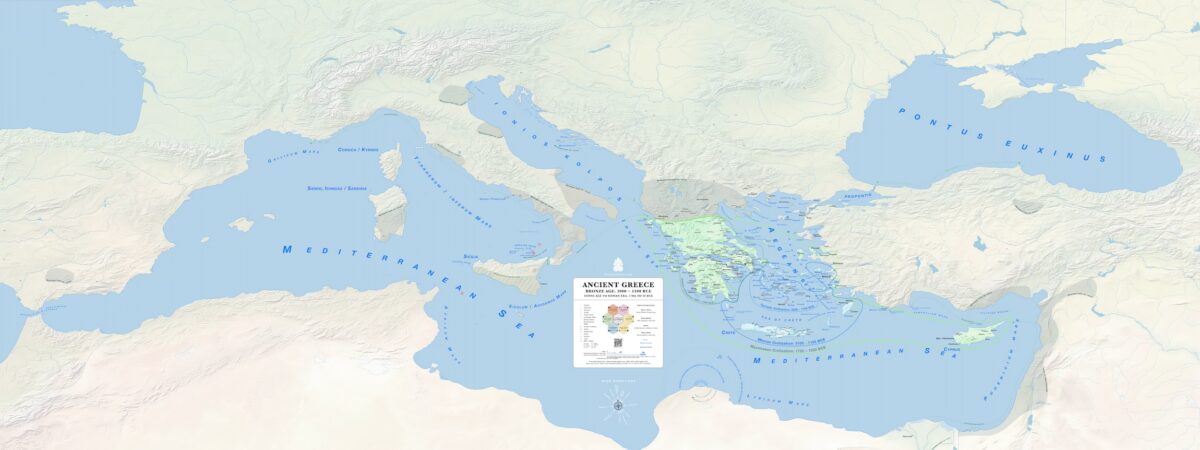

Greece is surrounded by water and sprinkled with islands within a few hours sail one from the other. Naturally, its people flourished for three thousand years by mastering the waves and establishing commercial networks and cities.

The Greek’s relationship with the sea began in the Mesolithic era, and remained special for three millennia. In Classical times Plato in Phased famously described the disbursement of Greek settlements around the Mediterranean as “frogs about a marsh”.

At the height of colonization (8th to 6th c. BCE), Greeks stayed as close to the shore as possible and rarely extended their residency too far inland.

Ships in ancient Greece were agents of sustenance, protection, wealth, and education. In their hulls, Greeks ferried goods, ideas, and military might throughout the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. They were vital to Greek life, and developed over the centuries from rough stone-age crafts to the sophisticated vessels of the Classical era.

Given the volume of maritime activity, images of ships are scant in the archaeological record but we get information about the ships of Ancient Greece and how they developed over four thousand years from shipwrecks, texts, and art depictions on pottery and sculpture.

Stone Age Ships

In Franchthi cave, in the mesolithic (13000 – 7000 BCE) stratum, archaeologist found the remnants of deep sea fish, and obsidian tools which chemical analysis showed it came form the island of Melos, 90 nautical miles of open sea away.

These are strong indications that the cave inhabitants and their contemporaries must have used boats.

Although, no vessel has survived from the Mesolithic era, some speculate that they were light boats made of reed similar to Papyrella boats used until recently on Corfu island. In 1987, an experimental papyrella was sailed in the Aegean to show that such a vessel could travel between islands.

Bronze Age Ships

Later, during the Bronze Age in the Aegean (3000 – 1000 BCE), Cycladic and Minoan civilization flourished in a robust maritime network.

Cycladic civilization was centered around the islands of the central Aegean, and the Minoan civilization was a “thalassocracy” (a state with primarily maritime realms, an empire at sea) that dominated Crete the Aegean islands and the coasts of mainland Greece and Anatolia.

Depictions of ships on Cycladic era “frying pans” and Minoan frescoes provide us with clues for what Bronze Age seafaring vessels were like.

The depiction on the “frying pan” from Syros (2800 – 2300 BCE) shows a long, multi-oared ship with a long vertical prow which is crowned with a fish sculpture (perhaps as a figurehead or a weather vane) sailing among spirals representing the orbital motion of the waves.

Minoan ship depictions similar to the Ship Procession Fresco from Akrotiri, and the amphora from Kolona from Aegina island, among other, show a vessel type similar to Egyptian ships of the era. Ships are depicted with a curved body that culminates in arched bow and prow, which were decorated with animal and floral themes (in the Ring of Minos depiction, the end of the stern shaped as sea horse’s head) or with a curved split tail.

A common galley in the Bronze Age era was the “penteconter“. Pentecoter galleys were about 90 feet long and were powered by 50 rowers–sitting in two rows along each side of the ship.

“It is at any rate clear that Odysseus’ ship had a crew of about fifty, and that the pentekontor, although Homer does not use the actual word πεντηκόντορος, was in use at the time of the Trojan War.” (Williams, 126).

Other ships of the era included smaller, twenty-oared ships and larger merchant vessels which were well equipped to carry food, goods, animals, and up to 250 men around the Mediterranean.

The Uluburun shipwreck which sank in 1300 BCE in the southern coast of Anatolia and carried copper ingots, luxury goods, and weapons gives us a good idea of the period ships and the kind of cargo they moved between ports in the eastern Mediterranean.

The Galley

Charles D. Stanton, in “Medieval Maritime Warfare” describes the environment in which the oared ship became a favorite vessel: “The Mediterranean had a deserved reputation for benevolence. Tidal effects were minimal and the winds were more predictable and less blustery, while the temperature was milder and more consistent across a relatively narrow band of latitudes, engendering fewer storms […] Moreover the sailing season was longer, March to Late October, with relatively clear skies enabling greater reliance on celestial navigation.

The topography of Mediterranean itself aided navigation. The northern coasts generally boasted lofty profiles with numerous landmarks. Safe havens in the form of bays, inlets, and galts were abundant, and several large, well watered islands dotted the sea from west to east.

All of these attributes promoted the development of the oared warship.

Galleys required relatively calm conditions, because their hauls had to be long and narrow in order to bring as many oars to bear as possible, and for freeboard, the distance of the waterline to the deck amidships chad to be fairly low so that the oars could enter the water at a nearly flat angle for the sake of efficiency.

The downside of these design constrains of course was that they made the ship susceptible to being swamped. Simply put, southern shipwrights built this swift but vulnerable vessels because the conditions permitted it. Thus the environment fostered the evolution of Classical oared warships like the Greek trireme.”

Galleys were invented in Egypt and were widely used in the eastern Mediterranean during the Bronze Age.

It took about 6 months to build a galley.

“The galley is an oared, wooden ship, built for speed, and used mainly for war or piracy. Mycenaean galleys were light and lean. The hull was narrow, as hydrodynamics dictated, and straight and low, to cut down on wind resistance and to ease beaching.

A pilot stood in the stern and worked a large-bladed single steering oar. (Incidentally, Homer gets this Bronze Age detail right: in his day galleys used the double-oared rudder.) The hull was decorated with a painted set of eyes in the bows and probably also with an image of the ship’s name, such as a lion, griffin, or snake. On the stem post was a figurehead in the shape of a bird’s head.

The galley was so successful that its form remained standard in the Mediterranean throughout Roman times.

But Bronze Age galleys lacked one refinement that marked their classical Greek and Roman descendants: the ram. The ram wasn’t invented until centuries later, possibly by Homer’s day.

Bronze Age naval battles were decided not by ramming but by crews wielding spears, arrows, and swords and engaging the enemy either from a cautious distance or up close in a hand-to-hand free-for-all.” (Strauss, 39).

The Rowers

In Mycenaean era, rowers were recruited from the King’s (wanax) realm. They were paid sometimes in land allotments, and their families were looked after while they were at sea. These men rowed the ships to battle, boarded and fought enemy ships at sea, and were also the infantry that fought on land.

The rowers sat on benches in two rows of about 25 on each side of the hull, in well ventilated galleries. Their heads stood above the open bulwark but were protected by leather screens. Each rower pulled one oar.

Under their bench, the rowers stored their kit which included a leather bag for grain, clay jars or skin bottles for water and wine, along with their weapons (a shield, a spear, and a sword).

Sailing in the Aegean Bronze Age

Homer describes the process of setting sail, sailing, and beaching the ships to camp in the Illiad:

“Twas night; the chiefs beside their vessel lie,

Till rosy morn had purpled o’er the sky:

Then launch, and hoist the mast: indulgent gales,

Supplied by Phoebus, fill the swelling sails;

The milk-white canvas bellying as they blow,

The parted ocean foams and roars below:

Above the bounding billows swift they flew,

Till now the Grecian camp appear’d in view.

Far on the beach they haul their bark to land,

(The crooked keel divides the yellow sand,)

Then part, where stretch’d along the winding bay,”

(Homer, 30)

According to Barry Strauss (40): “Greek kingdoms also maintained professional seamen, such as pilots and pipers (who kept time for the rowers), as well as sail weavers and other specialists. Naval architects supervised teams of skilled woodworkers in building and taking care of galleys.”

Homer’s epic poem, The Odyssey describes the trials of late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age seafaring Greeks in heroic detail, and reveals the deep fears of families whenever the men were away on long sea voyages: Penelope is sieged by suitors in the of absence of Odysseas who must overcome his own trials (the Cyclops, Aeolus Winds, Scylla and Charybdis, etc.) and temptations (The Lotus-eaters, Circe, the Sirens, Calypso) on his famed return home.

Odysseus is driven by nostos (νόστος: an Ancient Greek term describing the unbearable longing to return home), and Penelope by loyalty and immense patience. In the end, it’s the unwavering will of the protagonists to reunite in Ithaca that prevails.

It’s the stuff of legend, but no matter the century, people who have spent a few moons at sea would immediately relate to the ancient adventures because they echo the universal anxieties seafaring families all over the world endure.

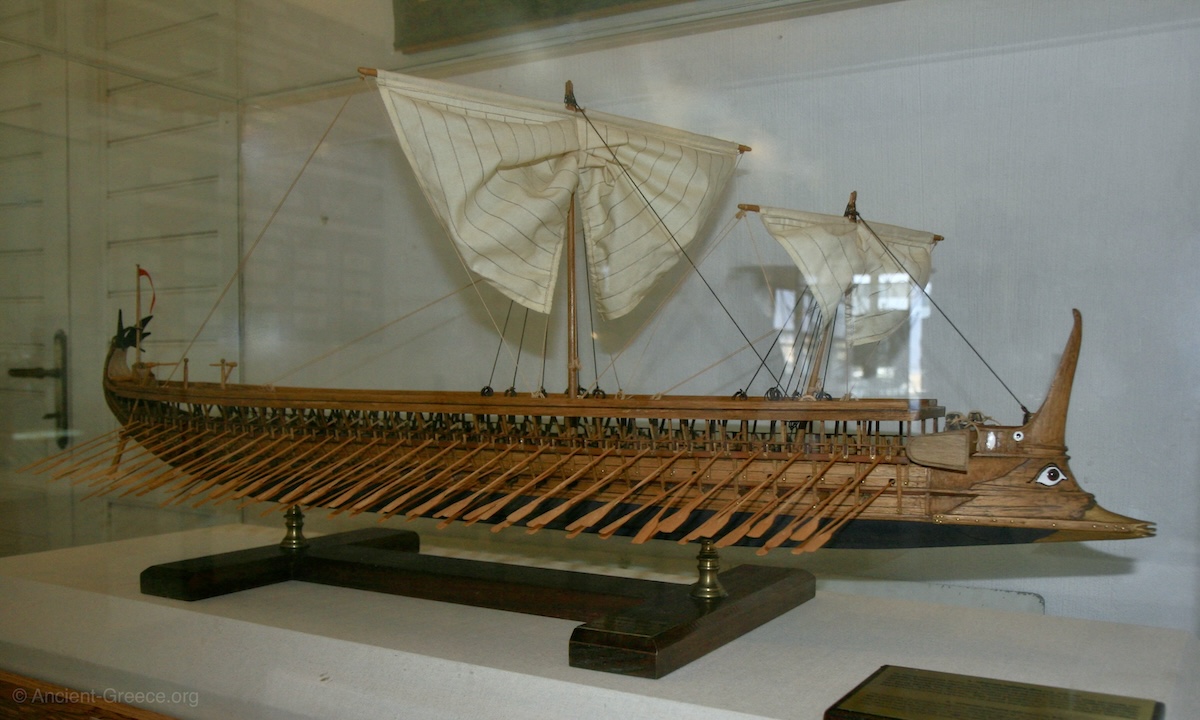

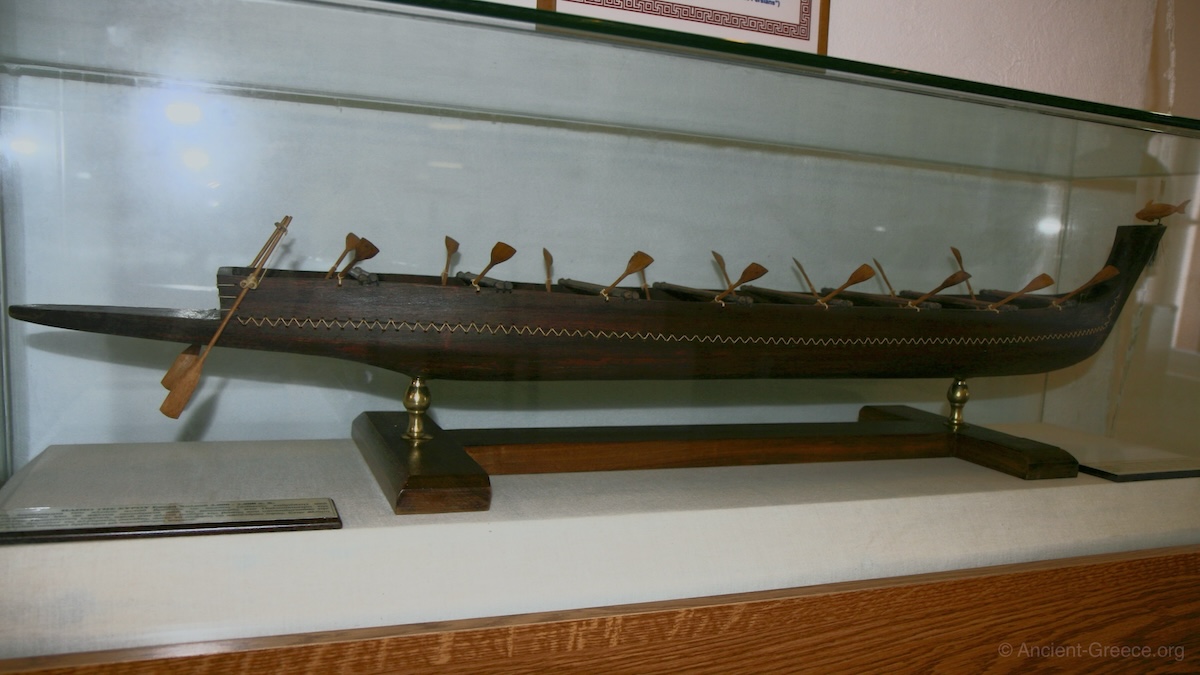

Photos of Ships from the Bronze Age

Archaic and Classical Era Ships

In the first millennia BCE (1000 – 30 BCE) ships continued to develop along the Eastern Mediterranean naval tradition established in the previous two thousand years but with some major innovations in design and functionality.

Trade in the Mediterranean increased, with large merchant ships crisscrossing the Mediterranean, establishing colonies and markets along the coasts of today’s Black Sea, Lybia, Italy, France, and Spain, and defending their land with advanced warships like penteconters, biremes and triremes. The major innovation in naval warfare came in the form of ships that fight each other instead of being platforms for troops.

Penteconters and Biremes

The early Iron Age is dominated by triaconters, (thirty-oared), and penteconters.

The largest ships of the early era were penteconters which were powered by 50 oarsmen, rowing side by side along each ship side.

Around the 8th century BCE, the Phoenicians added a second row of oars to create the bireme.

In this arrangement rowers did not sit one behind the other but in two levels that allowed more rowers to fit in the same size hull.

Biremes also had a ram to sink enemy ships and two steering rudders.

“The same period saw the development of the first two-banked ships—biremes—which carried the same number of oarsmen seated on two levels in a hull little more than half as long.

These stronger, more compact ships could support a raised deck for infantry, archers, and spearmen, which gave them a further offensive capability while keeping the rowers protected and out of the way.

For ordinary cruising, oarsmen probably rowed from the upper deck, while the lower position was used only in battle.

Eighth-century BCE illustrations show ships with rowers on two levels, but the first true biremes are depicted on reliefs from Nineveh showing Luli of Tyre’s flight to Cyprus. These show two banks of rowers; the lower oars protrude through ports cut in the hull (leather sleeves keep out the water), while the upper oars are on the gunwale level.

Rather than seating the oarsmen directly on top of each other, the benches are staggered, to keep the ship’s center of gravity low.” (Paine, 93).

The Trireme

Sometime after the 7th century BCE, Greek shipyards added an outrigger to the hull, to allow for a third row of oars, making it a “trireme” (τριήρης, meaning “having three rows of oars”), with each man pulling one oar.

The trireme was a long, maneuverable war vessel with three banks of oars (a total of 170 oarsmen).

A natural development from biremes, a trireme was a light and fast rowing ship with a powerful ram.

During classical naval warfare, the entire ship was a missile. In battle, foes maneuvered at sea with the goal of ramming and rupturing the joints of the enemy ship, thus sinking it or disabling it.

Triremes were the most advanced warships in the 5th century BCE, and instrumental in defeating the Persian invasions, and in the subsequent establishment of Athenian hegemony.

Their shallow draft allowed them to maneuver in shallow waters and to be beached easily every night. This flat bottom made the hull more unstable but more nimble in the hands of well drilled crews.

Triremes had square sails on removable masts for cruising when the winds were favorable.

According to Payne (94) the Athenians widened the upper decks of their triremes to accommodate more marines, a development that also allowed for protective screens to be fitted around the thalamians.”

The inlaid eyes on either side of the bow animated the hull and gave it the look of a sea creature prowling the waves.

Thucydides tells us that “the Corinthians were the first to approach the modern standard of naval architecture, and that Corinth was the first place in Hellas where triremes were built” (Strassler, 11)

The trireme played a big role in securing the development of the Athenian Classical age with their victory over the Persian fleet in the battle of Salamis in 480 BCE.

Trireme Speed

While the square sail allowed the crew to rest by cruising with favorable winds, triremes could reach impressive speeds under oars.

Thucydides records one nonstop passage from Piraeus to Mytilene that a trireme made in little more than twenty-four hours, about 7.5 knots, and Xenophon describes the 129-mile run from Byzantium to Heraclea on the Black Sea being covered at an average speed of about seven knots.

A replica trireme called the Olympias attained sprint speeds of seven knots in its first season. (Triremes were as much as 30 percent faster than penteconters, which remained the standard warship for smaller city-states lacking the resources to build or man larger vessels.)” (Paine, 95).

Trireme Rowers and Crew

Triremes were rowed by 170 oarsmen who were free men and were paid regular salaries. It was not uncommon during the Peloponnesian war for foes to attempt luring enemy rowers to defect for better pay.

Rowers were divided up into three ranks, which corresponded to three levels: “twenty-seven oarsmen per side on the lowest and middle banks (thalamians and zygians, respectively) and thirtyone thranites per side on the upper bank, for a total of 170.

As in biremes, the rowers were staggered, the zygians just above and forward of the thalamians, the thranites just above and forward of the zygians. To compensate for their height above the water—about 1.5 meters as opposed to half a meter for the thalamians—the thranite oars rested on an outrigger that gave the rowers greater leverage.” (Paine, 94).

The crew of a trireme included the 170 oarsmen, persons who kept time with flutes and drums, lookouts, boatswains, and helmsmen alongside a contingent of infantry, archers, and spearmen the number which fluctuates through time and mission.

The residency of sailors grew substantially in Classical Athens, to the point of influencing the balance of power that was hitherto concentrated in the hands of landowners, influencing thus the political system that became more inclusive. The need for manpower, especially for ship crews at certain times also influenced the Athenian city policies, allowing for more relaxed citizenship requirements.

However, sailors and sea merchants were not widely accepted and tensions between seamen and land aristocrats simmered. “But Salamis helped validate the notion of democracy in Athens (where the last tyranny had been overthrown only thirty years before), because the defense of the city involved citizens of humble birth, and not just contingents of wealthier hoplite soldiers.

The role of the former became permanent in the fifth century BCE as Athens nurtured an ever-expanding empire bound to the home city by its merchant and naval fleets”. (Paine, 105).

The Ship’s Ram

The ram was the pointed prow of the trireme or a bireme, and consisted of a strong wooden structure, a sort of projection of the keel, covered with bronze. Originally it took the form of a boar, and later – from the Classical period onwards – that of a trident.

“The idea of using ships to disable other ships rather than as simple troop carriers to be turned into floating platforms for hand-to-hand combat came to the fore around the ninth century BCE, the date of the earliest pictorial evidence of the ship’s ram.

This may have originated as a forward extension of the keel. In its more developed form it was capped with a heavy bronze fitting, thereby creating what was in essence a massive torpedo of great strength, speed, and hitting power, and designed to punch holes in enemy ships.” (Paine, 93).

The first record of ships’ use of a ram to sink enemies is from the battle of Alalia in 535 BCE where 60 Greek pentekontes ships from Phocaea defeated a Punic-Etruscan fleet of 120 ships while emigrating to the western Mediterranean and the nearby colony of Alalia (now Aléria).

Trireme Sailing and Tactics

Coordinating such fast, nimble, unstable, and powerful ship, especially during battle maneuvers took a lot of practice, and fleets with better trained crews, such as the Athenian fleet, had often the upper hand in naval battles.

Their weapon was speed, so they had to remain as light as possible. But the longer the ships remained at sea, the heavier they became as the wood soaked water.

Since warships of the time did not have the protective–and heavy–layer of lead sheeting that protected merchant ship hulls from the teredo worm, a wood-boring mollusk that thrives in the Mediterranean, it was imperative to keep triremes as dry as possible, so they were sheltered in dedicated sheepsheads when at port, or were pulled on beaches every night when away.

In battle, “trireme fleets sailed either in line-ahead formation (that is, aligned bow to stern), or line-abreast (side-by-side), the former being standard for cruising, the latter for going into battle under oars. […] As a defensive measure, ships could maneuver themselves into a circle with their rams pointing outward, against which the best offense would be to circle around the group—a maneuver called a periplous—before turning into the enemy ships. Another form of periplous involved a ship’s wheeling around on a pursuing attacker to strike it from astern or abeam.

A distinct maneuver was the diekplous, “sailing through and out,” in which ships in a line-abreast formation rowed through the enemy line before coming about to strike the ships from astern, the most vulnerable part of a trireme.” (Paine 95).

In his History of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides describes such naval tactics with vidid details:

“The Peloponnesians ranged their vessels in as large a circle as possible without leaving an opening, with the prows outside and the sterns in; and placed within all the small craft in company and their five best sailers to move out at a moment’s notice and strengthen any point threatened by the enemy.

The Athenians, formed in line, sailed round and round them, and forced them to contract their circle, by continually brushing past and making as though they would attack at once, having been previously cautioned by Phormio not to do so till he gave the signal.

His hope was that the Peloponnesians would not retain their order like a force on shore, but that the ships would fall foul of one another and the small craft cause confusion; and if the wind which usually rose toward morning should blow from the gulf (in expectation of which he kept sailing round them), he felt sure they would not remain steady an instant.

He also thought that it rested with him to attack when he pleased, as his ships were better sailers, and that an attack timed by the coming of the wind would tell best.

When the wind came up, the enemy’s ships were now in a narrow space, and what with the wind and the small craft dashing against them, at once fell into confusion: ship fell foul of ship, while the crews were pushing them off with poles, and by their shouting, swearing, and struggling with one another, made captains’ orders and boatswains’ cries alike inaudible, and through being unable for want of practice to clear their oars in the rough water, prevented the vessels from obeying their helmsmen properly.

At this moment Phormio gave the signal, and the Athenians attacked. Sinking first one of the commanders’ ships, they then disabled all they came across, so that no one thought of resistance for the confusion, but all fled for Patrae and Dymesa in Achaea.” (Strassler, 429).

Trireme Building

In the early 5th century BCE, the building of a fleet of triremes, financed by the Laurion Mines, brought a flurry of ship building activity to the coast of Attica that produced 6-8 triremes per month for 6 years, and “this would produce up to two hundred in the period July 483 – May 480; between then and July 480 perhaps another dozen were laid down.

The total number available at the outset of the campaign was over 250. The balance must have been made up with the best of the fleet already in existence.

That so much was achieved in so short a space of time – a crash building programme if ever there was one – is a remarkable tribute to Athenian resourcefulness and perseverance.

Crews were mustered and trained. Skilled craftsmen poured into the Piraeus dockyards. Contracts were placed abroad for ropes and sails and – above all – first-class timber.

Two hundred triremes, for instance, would require no less than 20,000 oars, cut from best pine or fir. (It was no accident that throughout the fifth century BCE the King of Macedon figured so prominently on the Athenian VIP list) Attica’s trees were being used up faster (what with goats and charcoal-burners) than the forests could re-grow themselves, so that almost all lumber had to be imported. (Green, 57).

The Cost of a Trireme

According to Karan (61) each trireme cost one talent to build, and it cost one talent to pay the crew of a warship for a month. Athens at the beginning of the Peloponnesian war had 200 triremes in service, while the annual gross income of the city of Athens at the time of Perikles was 1000 talents, with another 6000 in reserve at its treasury.

During the Classical era in Athens, wealthy citizens were responsible for fitting the triremes and paying the crew on behalf of the state. They were called trierarchs.

Photos of Ships from the Archaic and Classical Eras

Hellenistic and Roman Era Ships

The Hellenistic age saw minor developments in ship construction and style, but a huge increase in trade volume.

Triremes dominated the seas, and 2nd century BCE Roman triremes had a heavy tower at the prow and the deck.

New ships are variations of old designs with attempts to fit more oars like Polyremes (Quadrireme, Quinquereme, etc) and Catamarans. Consequently, on the whole, ships in the post-Classical era are larger, but some lighter and faster variations emerged in improved designs from the Classical Era (triacontors (τριακόντοροι, triakontoroi, “thirty-oars”) and pentecontors (πεντηκόντοροι, pentēkontoroi, “fifty-oars”).

These included the Lembos (from Greek: λέμβος, “skiff”, in Latin lembus), the hemiolia or hemiolos (Greek: ἡμιολία [ναῦς] or ἡμίολος [λέμβος]) that first appeared in the 4th century BCE. They were mainly used for scouting but they were also used by pirates.

Photos of Hellenistic Era Ships

Ancient vs. Modern Ship Building Methods

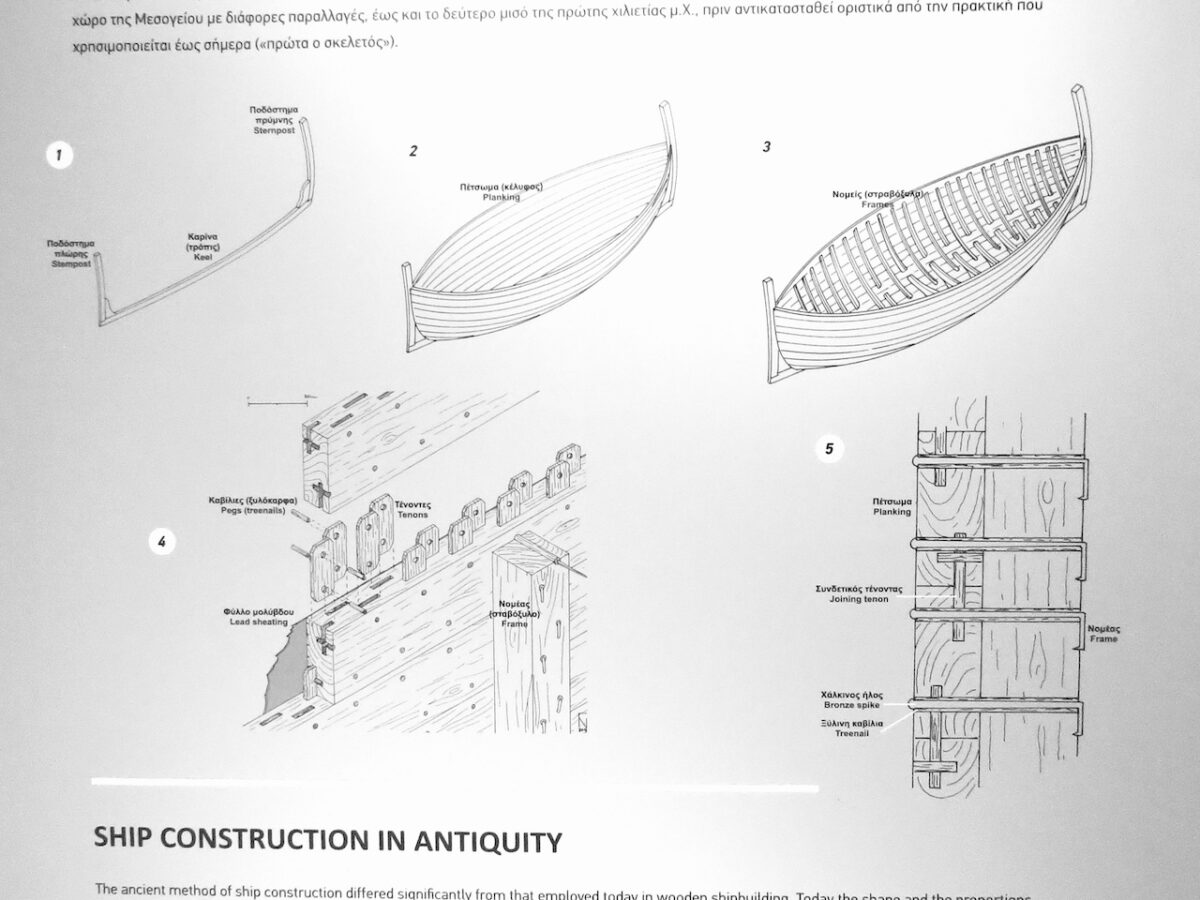

The ancient method of ship construction differed significantly from that employed today in wooden shipbuilding. Today the ship’s keel and frame is built first and then the hull planks are fitted around it.

In Ancient Greece, the keel was built first and then planks of the hull were fastened to each other to form the shell. Then νομείς (στραβόξυλα, frames) reinforced the hull from the inside.

“Shell-first construction” dominated Mediterranean ship-building tradition from the Late Bronze Age until the second half of the first millennium AD, when it was gradually replaced by “skeleton first construction”, the method still used today.

Description of Shell-First Ship Construction

A good description and illustration was displayed in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens information accompanying the Antikythera Shipwreck exhibition:

“The ancient shipwright began the building of a ship by setting up the keel. (Fig. 1)

The stem and the sternposts were then mounted, and the builder began to shape the hull.

Long planks on superimposed lines were attached on both sides to one end of the ship and, given the desired curve, fastened then to the other end. (Fig. 2) Superimposed rows of planks were edge-joined and connected to each other with wooden tenons fitted into mortises cut in both edges of each individual plank.

The joinery was finally held in place with treenails driven into holes, drilled after the tenons had been fitted into the planks. (Fig. 3)

Frames were inserted in the structure only after the external hull was completed to a certain extent, first the floor timbers followed by the half frames and the futtocks. (Fig. 4)

The attachment of the frames to the planking started with the drilling of holes through planking and each attached frame, and the insertion of long wooden treenails into the holes.

Finally the wooden treenails were transfixed by bronze spikes, hammered from the external side of the planking. (Fig. 5)

Related Pages

The 2018 role-playing action game Assassin’s Creed Odyssey by Ubisoft offers the opportunity to engage in some spectacular imaginary sea battles where the player gets to commandeer a trireme. While fiction, the game ramming sequences offer the unique experience of the trireme’s bone-crushing impact on an enemy ship’s hull.