On this page:

The Antikythera Shipwreck is a 1st century BCE underwater shipwreck and archaeological site, located 25 meters from the coast of Antikythera island, Greece, at a depth of about 50 meters.

The cargo ship’s final voyage started in an Aegean port (speculated to be either Miletus, Pergamum or Delos)and was destined for was probably Rome, but it sank en route sometime between 60 and 50 BCE.

Underwater excavations have yielded a number of important ancient artifacts, including the renown “Antikythera Mechanism”, and exceptionally-crafted sculptures and luxury goods of the era.

Among the retrieved objects we also find reminders of those who rode the waves and perished with the ship on the fateful day of her sinking. Their remains and everyday objects tell us of their vessel and their daily life at sea.

The objects raised from the wreck speak of a large cargo ship that carried luxury goods from various sites around the Aegean to Italy.

The Ship

According to the National Archaeological Museum:

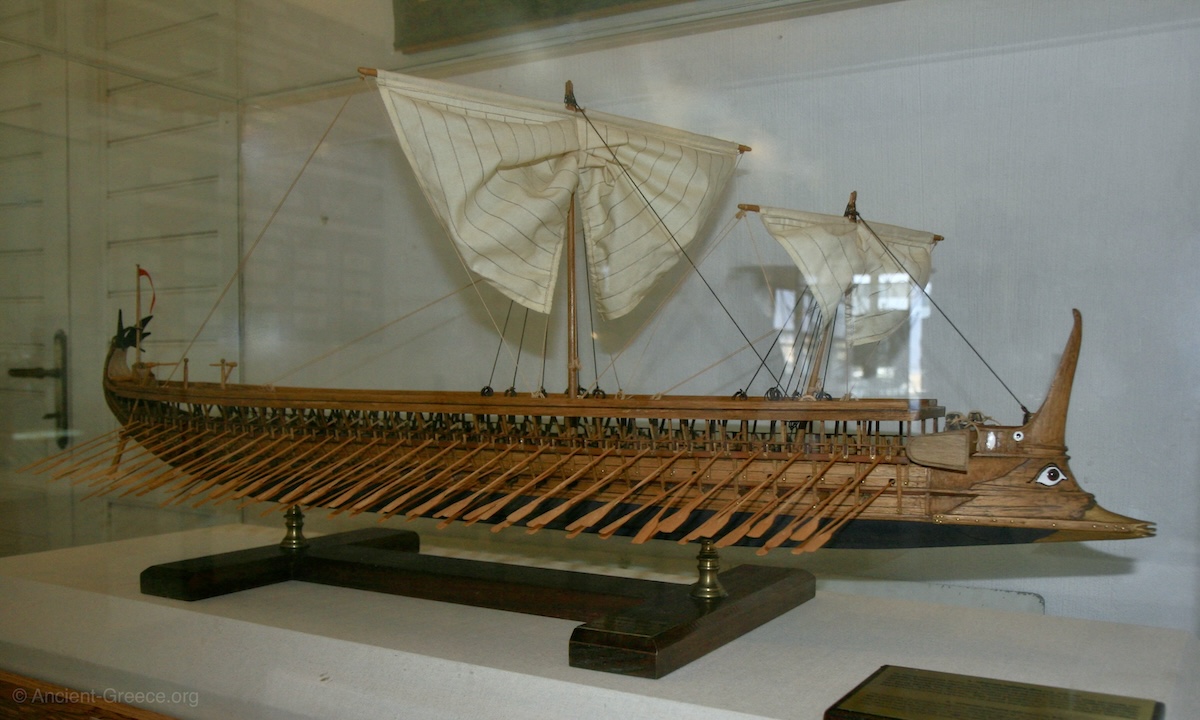

“The ship that sank off Antikythera was a freighter (holkas), of an estimated capacity of about 300 tons.

Her physical remains are meager, and the wreck, at a depth of some 52 m., has not yet been mapped. Parts of the stern and the prow have not been identified.

The ship’s hull was built from single planking, in accord with the ‘shell-first’ technique (Read more about ships in Ancient Greece).

The wooden pegs and tenons that connected the planks of the Antikythera ship were made of oak, and the planks of elm. The exterior surface of the hull below the waterline was sheathed with thin sheets of lead.

In these photos: Lead drainage pipe, lead sounding weights, and bronze rings associated with the ship’s mast.

“The discovery of two sounding weights for measuring depth and ascertaining the nature of the seabed (katapeirateriai) gives some indication of the ship’s size and the voyages on the high seas that it undertook.

The port of departure of the ship that sank with its precious cargo in the sea off Antikythera in the 1st c. BC remains unknown. It was probably Delos or, according to a different view, a port on the Asia Minor coast. Its destination, however, must have been Rome.” (Text at the Antikythera Shipwreck exhibit).

Life Aboard

A male of about 20-25 years old, a young female, and a 15 year old of unknown sex are the three individuals identified as the ship’s occupants from osteological analysis of the remains found among the shipwreck.

Excavations of the shipwreck recovered 22 bone pieces, and no complete sceletons.

We cannot be sure these were the only humans aboard nor can we assume they were crew members, as cargo ships occasionally ferried passengers, but we get a glimpse of their daily life from the objects they left behind. The Antikythera Shipwreck was the first to yield human remains.

“The Corinthian roof tiles suggest the existence of a roofed area on the deck, which very probably was used to protect, by means of the tiles, the retractable wooden doors of the loading hatches and also served for the preparation of food.”

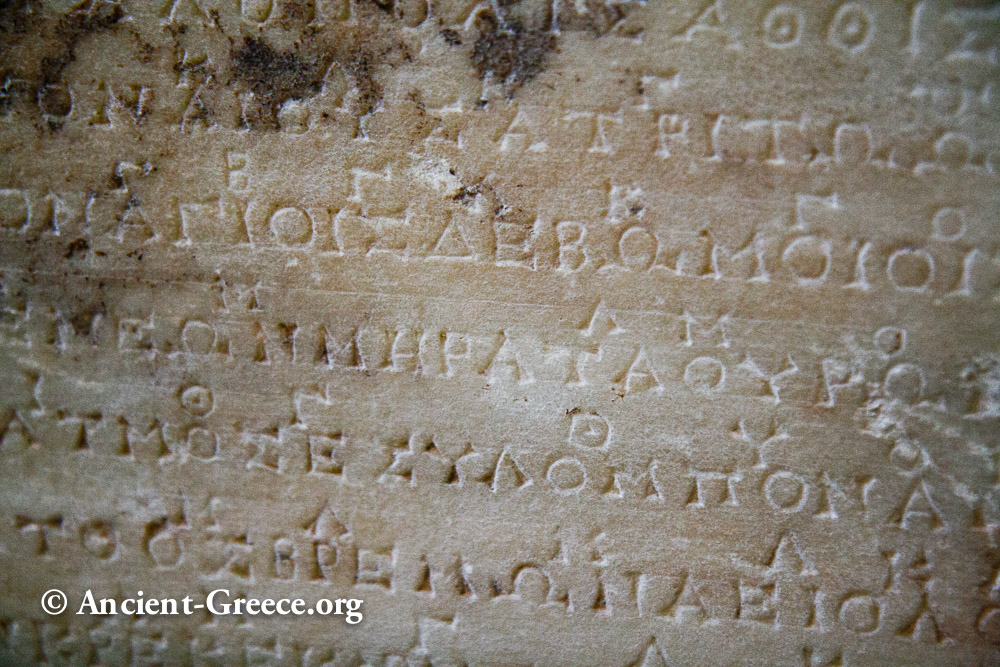

The challenging underwater excavations have raised several cooking pots–some with traces of burning, dinnerware–some with the owner’s name incised, a mortarium for grinding seeds, liquefying vegetables and herbs, and stirring liquids, and a manually operated quern for grinding grain.

The crew’s diet included fish, olives, snails, salted meat, and flavored wine identified from resin inside a jar and a krater.

They used clay and metal lamps for lighting aboard ship, as suggested by several recovered examples, one of which shows traces of burning. The filter jugs are considered to have been used as oil containers for the lamps.”

Several board game pieces were also recovered from the wreck.

The Cargo

During the centuries of Roman conquest of the Hellenistic world, works of art, especially sculptures, were assembled in Rome from all over the Greek world, either as spoils of war or as collector’s items. The ship that sank off Antikythera was carrying such a cargo.

The recovered artifacts include high quality goods in the form of bronze and marble sculptures, smaller statuettes, gold and silver jewelry, fine glassware, as well as clay vases, fragments of furniture, and caurseware pottery.

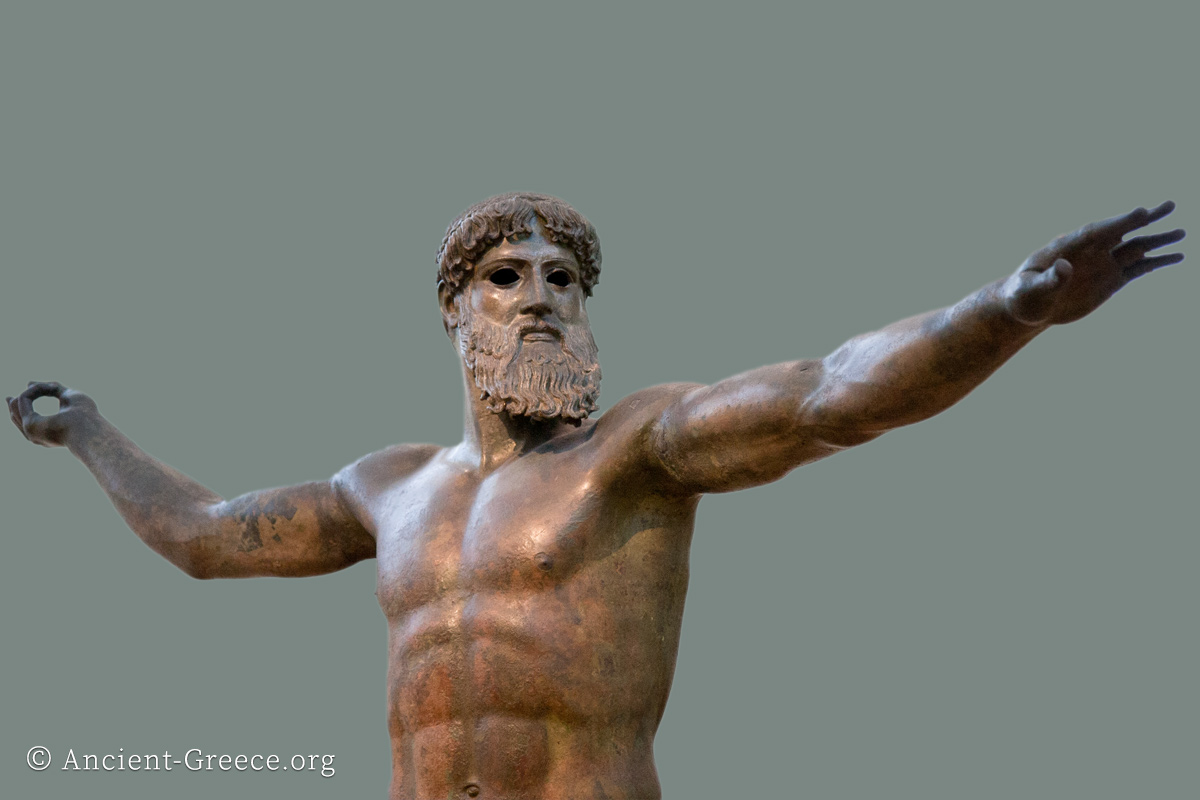

The first object retrieved from the bottom of the sea was the right arm of a bronze statue of the 3rd c. BC depicting a philosopher, which is attributed to Euphranor, sculptor of the 4th c. BCE, or his school.

The bronze statue known as Antikythera Youth (340 – 330 BCE) has been identified with Perseus holding the head of Medusa. More probably, however, it depicts Paris holding the “apple of Strife”, ready to award it to the most beautiful goddess, Aphrodite. The statue is attributed to the Sikyonian sculptor Euphranor or to a sculptor belonging to the Argive-Sicyonian School which continued the Polykleitan tradition until the late 4th c. BCE, most probably Kleon the Sicyonian.

The bronze statuettes from Antikythera are classicizing creations mainly of the 2nd c. BC that were influenced by sculptures of the Classical period.

The cargo included finely-crafted and rare glassware, most likely part of luxury wares destined for the markets of Rome.

“Raised from the depths during the investigations of 1900-1901 and 1976, these objects represent the best-known glass-working techniques of the Hellenistic age. Moreover, the monochrome and polychrome vessels provide a complete sampler of Syro-Palestinian and perhaps also Egyptian production of glassware in the first half of the 1st c. BC, while simultaneously offering the first reliable evidence concerning glass trade between East and West. The excavations on Delos, an international centre for transit trade during this period, have yielded glass finds of the same types as those found in the shipwreck.”

Among the finds, the Antikythera Mechanism stands alone as one the most unique of ancient objects discovered anywhere to date.

The Antikythera Mechanism

The Antikythera Mechanism is dated to the second half of 2nd century BCE.

It is accepted that the machine is a calendrical computing machine: it determines the time on the basis of the movements of the sun and moon, the relationship between them (eclipses), and the movements of the other stars and planets known at that period.

The mechanism has 32 gear wheels and plaques bearing Greek inscriptions relating to the signs of the zodiac and the months.

It was probably made at the School of Poseidonios on Rhodes. Cicero, who visited the island in 79/78 BC, reports that a similar device was made by the Stoic philosopher Poseidonios of Apameia.

The design of the Antikythera mechanism appears to follow the tradition of Archimedes’ planetarium devices, and to be connected with sundials. Its operation is based on the use of gear wheels.

The differential gear assembly used to take the difference between two rotations is first found in the Antikythera mechanism, which is one of the most important achievements of ancient technology.

The Museum’s reconstruction and explanation are helpful in understanding the form and function of the mechanism. It features a replica of the mechanism with explanations on what each function does:

Historical Context

The Antikythera shipwreck is on a well established maritime route that served a robust maritime trade between the cosmopolitan Hellenstic East and Republican Rome.

The affluent Italian aristocracy had a healthy appetite for works of art and luxury goods from the east, so Rome and several other cities in Campania, Etruria, Laium, and Sicily became busy hubs for trade of goods and loot from the rapidly expanding empire.

The Antikythera Shipwreck was part of this network.

“From the late 2nd c. BC the members of the upper classes in Italy, in addition to possessing a house in the city, also owned a number of villas in the countryside and on the coast, fitted with comfortable living quarters and often possessing an industrial wing.

The rooms reserved for reception and recreation were furnished with paintings, mosaic floors and sculpture, following the model of the palaces of Hellenistic monarchs, Greek sanctuaries and philosophical schools, and thus displayed the wealth and cultivated tastes of their owners.

The Roman demand for Greek art works resulted in a great deal of it decorating Italian and Sicilian villas.

These individuals retreated to their villas, in pursuit of escape from everyday concerns and business matters and looking forward to leisure time and pleasures.

Around 70 BC the Roman orator and politician Cicero frequently corresponded with his compatriot Titus Pomponius Atticus, an intellectual and banker settled in Athens, regarding the purchase of marble and bronze sculpture and its transport on his behalf from Piraeus to Italy via sea.

With these works of arts Cicero would embellish some of his eight villas. Orders for works of art of this kind may have been the reason for chartering the ship that was sank off Antikythera.

Seafaring was a risky business in ancient times and the bottom of the Mediterranean is sprinkled with shipwrecks like the Antikythera one.

Statistical analyses show that the danger of shipwreck in open water navigation during the Classical-Hellenistic periods was 1:20 to 1:30. Most wrecks have been identified in the western Mediterranean, primarily along the Italian west coastline. The fact that most of them belong to the Late Hellenistic period, era of the Roman Republic, suggests a peak in maritime transport of works of art and products during this period.

Historical Photos and Documents

Famously, the ship was discovered accidentally by sponge divers in spring 1900 off the island of Antikythera. Government documents of the era show the importance of the find. The work of retrieval began within the year.

Related Pages

Tools of the Era

Bronze medical instruments show the level of craftsmanship standards of the Hellenistic era.

Heron’s Odometer is an example of a machine with gears from the period. This type of odometer was likely invented around the 3rd century BCE, and was widely used during the late-Hellenistic Period. In 27–23 BCE Vitruvius described the device invented by Archimedes of Syracuse (c. 287 BC – c. 212 BC).

Photographs and information from “Το Ναυάγιο των Αντικυθήρων” (The Antikythera Shipwreck) 2013 exhibit at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, Greece.