On this page:

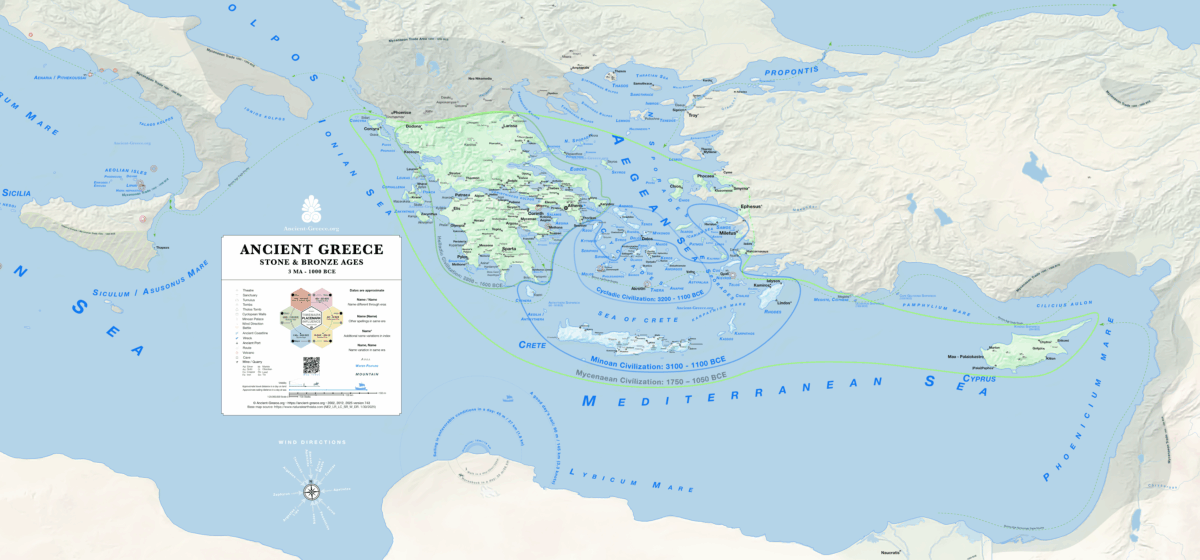

What has survived to our day from Minoan art provides insight into the culture that flourished in Crete during the Aegean Bronze Age.

The art of the Minoans speak of a society of joyous disposition, in touch with their environment, and in awe of the logical order of the natural world. Above all, the unearthed artifacts reveal a people who had developed a high degree of self-respect and a keen eye for observing and adopting to their physical environment.

Minoan Art reached its apogee during the Neopalatial era, reflecting a period of extraordinary development, while later, during the Postpalatial period it echoed the decline of Minoan Civilization.

Palaces

Most of the Protopalatial (1900 – 1700 BC) palace buildings were destroyed around 1700 BC and new ones were constructed on their ruins, so the archaeological clues regarding, form, style, and function are limited.

We do know that, compared with other societies of the same era, the inhabitants of Crete did not emphasize with their architecture temples, tombs, or fortresses. Instead, palaces were built mainly to serve the organizational, and administrative needs of their society.

Minoan Palaces, besides being places of administration, were also gathering places for commercial exchange, artistic production, worship, and storage of agricultural produce. All palaces contain buildings to serve such needs and their practical design was ideal for the palaces of the Neopalatial period.

Nowhere have we seen palaces with defensive walls, a trend that continued to the end of the Minoan civilization, and is a tribute to the naval supremacy of Crete throughout prehistory.

After their abrupt destruction, the palaces of the previous generations were rebuilt during the Neopalatial Period (1700 – 1400 BC) to be even more elaborate than the ones they replaced. The new palaces were built on the ruins of the old ones, and in many cases, older structures were incorporated into the new design, and when this was not possible, the old ruins were completely covered with earth and new buildings were constructed on top.

They all exhibited similar architectural elements with the protopalatial buildings. The main feature of all palaces was the central courtyard which was framed by many buildings and probably acted as the main everyday gathering place. Large circular silos, probably for storage of grains, appear near the entrances of most major palaces and villas, while an extensive network of storage magazines occupy large parts of the palaces.

There were also artist’s workshops which were directly related to the commercial activity that took place, elaborate rooms for formal functions we now call throne rooms, cult chambers, and theaters where people could gather during special events.

The palaces exhibited several unique characteristics in their multi-storied buildings. Long walls were usually interrupted by recesses which broke the monotony of the extended planes and provided a play between light and dark as shadows were always captured throughout the day. Large exterior staircases seemed to also play an important function in Minoan architecture, leading to important parts around the palace and bestowing a sense of awe to the visitor.

Columns in Minoan palaces play an important role in dividing space as they allowed open shaded areas to shelter the inhabitants from the intense sun rays that shone down for most of the year. It is also believed that the column had ritual significance for the culture and was placed in prominent places to serve as metaphor more than as a functional element.

One good example of how staircases and columns provided focal points is the palaces of Phaistos where two grand staircases converge at the corner of the theater and the courtyard. Ascending the impressive staircase to the East a visitor is confronted with the complex architecture of the west propylaea which consisted of a wide landing, a porch with a central column, a portico, and a light well.

Pottery

During the Protopalatial Period (1900-1700 BC), as Minoan society developed its complex organization, the introduction of the potter’s wheel allowed efficient production of vessels with thin walls and subtle, symmetrical shapes.

The Kamares ware is the most characteristic style of this period. The pottery style developed in Kamares was characterized by very thin walls, robust swollen curves, elegant spouts and decorations and its beauty made it very popular in Crete as well as in Egypt and Syria where it was exported.

The characteristic elegance of form of Minoan potter is complemented by the dynamic lines of naturalistic scenes that decorate the surfaces. The sweeping curves of the profile are emphasized through bold lines that traverse the surface and radiate in their contrast between dark and light values.

This vigor of form, the spontaneity, and the fluidity of the early pottery was transformed to a more stylized manner of creation in the late Neopalatial era. This aesthetic metamorphosis reflects a turn in philosophical attitudes which became more interested in formalist abstraction and a dissociation with naturalism.

See more Minoan Pottery examples in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum…

Frescoes

Plastered walls from the Minoan palaces and villas that have survived to our day provide a precious portrait of life in Crete during prehistoric times.

The figures and scenes painted in the Minoan frescoes display the familiar Egyptian side view with the frontal eye, as well as the sharp outlines in solid color.

The Egyptian influence when it comes to painting seems to stop there as the Minoan frescoes distinguish themselves from the products of other Mediterranean cultures in many ways. They are characterized by the small waist, the fluidity of line, and the vitality of character bestowed on every painted figure. Minoan stylistic conventions emphasized elasticity, spontaneity, and dynamic motion, while the colors and high-contrast patterns instill an elegant freshness to characters and nature scenes alike.

While the Egyptian painters of the time painted their wall paintings in the “dry-fresco” (fresco secco) technique, the Minoans utilized a “true” or “wet” painting method. Painting on wet plaster allowed the pigments of metal and mineral oxides to bind well to the wall, while it required quick execution.

The nature of this technique allowed for a high degree of improvisation and spontaneity and introduced the element of chance into the final art. Since they had to work within the time constrains of the drying plaster, the painters had to be very skillful, and their fluid brush strokes translated into the graceful outlines that characterize minoan painting. For this reason, the true wet method of painting was most appropriate for the fluid moments of life and nature scenes that the Minoans favored, which contrasted sharply with the strict stylization and stereotyping typical of frescoes from other Mediterranean cultures of the same time.

The figures of Minoan frescoes are depicted in natural poses of free movement that reflect the rigors of the activity they engage with, an attitude characteristic of a seafaring culture accustomed to freedom of movement, liquidity, and vigor.

See more frescoes in the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion…

Jewelry

Exquisite metal works were created in ancient crete with gold and copper imported from abroad.

The Minoans employed several techniques to shape various metals into utilitarian objects and works of art. They mastered the techniques of lost wax casting, repuse (embossing), gilding, faience (grannulation), and nielo.

The bee pendant (image above) is a good example of the artist’s mastery of the demanding process of faience, during which tiny beads of gold are adhered to the surface of the cast jewelry with a special low-heat solder alloy. This is a technique most likely learned from the Syrians and with whom the Minoans had regular contact.

The Minoans introduced the niello technique to the Mycenaeans, who used it to create black, bold outlines on gold decorations, and mastered the delicate process of gilding objects with gold leaf (extremely thin sheets of hammered gold foil). The Harvest Rython (image below) and the Bull Rython’s horns were gilded with gold leaf.

Minoan Sculpture

Very little sculpture from Minoan Crete has survived since most of it was not monumental, and instead consisted of small artifacts dedicated to gods or kings or ritual objects and vessels.

One of the best known examples is the Snake Goddess fetish which exhibits many stylized conventions with the geometric division of the body and dress, while its frontal pose reminds us of Mesopotamian and Egyptian sculpture. The extended arms holding the snakes however add animation to the static pose. The statuette appears to be a goddess or high priestess, and the dress which covers the body all the way to the ground while leaving the breasts exposed was typical of Minoan women attire.

See more Minoan statuettes in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum…