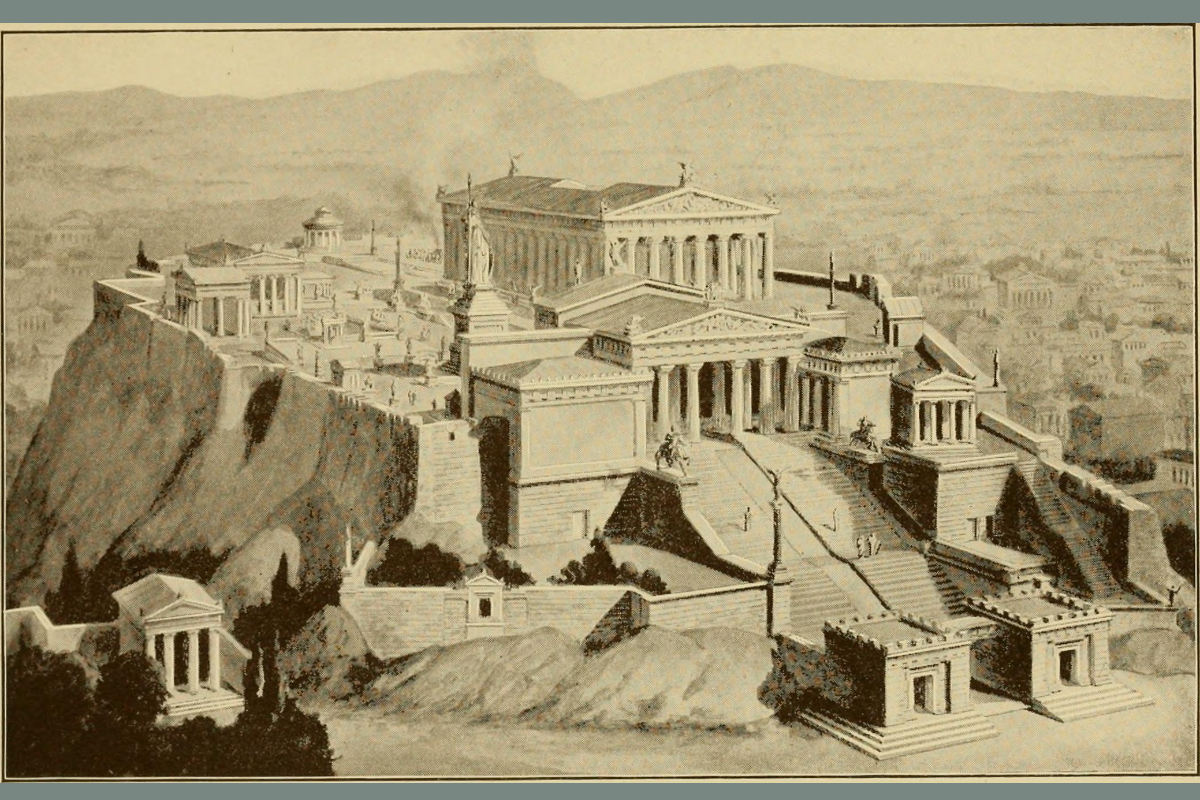

Photographs of the Parthenon metopes from the Acropolis, and the British museums.

The Parthenon metopes were visible on the exterior of the temple above the colonnade. They were sculpted in deep relief and surrounded the temple on all sides. Most Greek temples had few decorated metopes, but in the Parthenon all ninety-two metopes were decorated on all sides with scenes from Greek mythology.

While the narrative differs from side to side, the metopes are bound thematically by a common didactic theme: the triumph of refined logic over uncontrolled instincts.

Each side of the Parthenon depicts a different mythological and historical theme. The metopes in the east facade (or front) of the temple depicted the Gigantomachy, or the battle between the gods and the giants. The west metopes depicted fights between Greeks and the Amazons (or Persians), while the north and south metopes included scenes from the Trojan War and the Cenauromachy respectively.

The original metopes were painted and had metal embellishments like weapons, as was customary for Ancient Greek sculpture.

Facial expressions appear exaggerated in many of the figures whose heads have survived centuries of abuse by nature and man alike. Most are missing because they were systematically damaged first when the Parthenon was converted to a church in antiquity and the “nude” (and pagan) sculptures were chiseled off. Further damage occurred in subsequent years while the building was adopted for different purposes, and when the Venetians scored a direct hit on the Parthenon with a mortar shell during their battle with the occupying Turks who stored their gunpowder in the temple.

The Colors of the Metopes

We know that the metopes were painted in ancient times, but even with scientific analysis we cannot be certain if the colors were vivid or pale, or what the finished sculptures looked like. Either way, the effect color on relief forms would make the action in the panels even more dramatic and animated, as well as more visible from a distance.

Several different interpretational drawings have been produced in modern times by scholars. They are educated facsimiles at best, but they do provide some guidance on how the metopes might have looked colored. According to Dr. Αγγελακοπούλου, the 19th century conclusions on color application by Faraday and Lenderer are in concert with the 21st century finds.

The colors faded through the centuries, but pigment remnants can still be traced on the ancient stones. In modern forensic analysis by ΥΣΜΑ (Acropolis Restoration Service) , the background of the metopes shows some remnants of red and red-orange pigment, while the flat bands that frame the top and bottom show remnants of blue, including Egyptian blue on the top band. (Αγγελακοπούλου, 1:01:18).

We know some of the colors that were used on the metopes, but the passage of 2500 years have erased the painting, so we are left to only imagine what the original sculptures looked like with color.

Read more about the colors of the Parthenon…

Exceptional craftsmanship

Exceptional craftsmanship characterizes the rendering of the figures. The tension of the muscles, the push of the bone against the flesh, and even bulging veins are clearly visible on the forms.

These are surprising details for sculptures that were to be seen from a considerable distance as they were displayed as part of the Doric frieze that, alternating with triglyphs, dressed the perimeter of the entablature above the peristyle. Perfecting every detail of the goddesses house could be a sign of reverence. The temple was built for her after all.